Impersonation fraud has emerged as one of the most consequential identity risks facing payment ecosystems in 2026. Unlike traditional fraud patterns that rely on stolen credentials or compromised cards, impersonation works by credibility. Fraudsters do not simply break in; they convincingly pretend to be legitimate customers, exploiting trust built across digital channels, customer support interactions, and payout workflows. This makes impersonation harder to detect, slower to surface, and more damaging when it succeeds.

What makes impersonation particularly dangerous is that it rarely appears at checkout alone. It manifests across the customer lifecycle during login, when contacting support, when changing payout details, or when introducing new payee instructions. Payments and payouts are often the final step, not the entry point. As fraud models evolve, detecting “someone pretending to be you” requires linking identity, behaviour, and intent across time, channels, and transactions, rather than relying on isolated signals at the moment of payment.

- Where Impersonation Appears Across the Customer Lifecycle

- Where Impersonation Appears Across the Customer Lifecycle

- Model Design: Linking Identity, Device, Behaviour, and Transaction Intent

- Signals That Expose Impersonation: When Behaviour Stops Matching the Identity

- Tools That Stop Impersonation Without Breaking Trust

- Operational Flows: Blocking Impersonation Without Creating Customer Hostility

- Why Payout Risk Must Be Scored Differently From Purchase Risk

- Conclusion

- FAQs

Where Impersonation Appears Across the Customer Lifecycle

Impersonation fraud rarely succeeds in a single move. It is typically exploratory and incremental, with fraudsters testing credibility at multiple points before attempting to extract value. Each interaction provides a signal both to the attacker and to the defending systems and it is the accumulation of these signals that defines impersonation risk.

Login and authentication attempts

The earliest signs of impersonation often appear at login. Unlike brute-force attacks, impersonation attempts may succeed technically while still feeling “off” behaviourally. Credentials may be valid, but the way they are used diverges from historical patterns. On their own, these signals are weak. In context, they often mark the start of a longer impersonation attempt.

Customer support and account recovery interactions

Customer support is one of the most exploited surfaces for impersonation. Fraudsters use partial information, urgency, and plausible narratives to bypass controls designed for genuine users who have simply forgotten credentials or need help.

Typical impersonation behaviours include:

- Requests framed around “lost access” or “urgent account recovery”

- Overconfidence combined with gaps in contextual knowledge

- Attempts to steer conversations away from stronger verification steps

Because these interactions are human-mediated, they are especially vulnerable when identity context from other channels is not visible to support agents.

Payout and withdrawal changes

Payout-related actions are where impersonation risk peaks. By this stage, the fraudster is no longer probing; they are attempting to monetise access. Changes to payout destinations, withdrawal methods, or timing often follow earlier credibility-building steps.

Why lifecycle visibility matters

Industry fraud research increasingly shows that impersonation is not confined to one channel or moment. Studies into identity fraud patterns highlight that a significant share of attempts involve impersonation claims spread across multiple interactions rather than single-point attacks. This reinforces the need to evaluate identity credibility across time and touchpoints, not just at checkout or payout approval.

Where Impersonation Appears Across the Customer Lifecycle

Impersonation fraud does not announce itself with a single high-risk event. It unfolds gradually, often beginning with actions that look routine and only later revealing malicious intent. Fraudsters probe systems and people, learning where friction exists and where trust can be exploited. By the time a payment or payout is requested, the groundwork has often already been laid.

What makes impersonation particularly dangerous is that each interaction, taken alone, can appear legitimate. The risk only becomes visible when those interactions are connected across time, channels, and intent.

Early signals during login and access attempts

Impersonation frequently begins at the point of access, but not in the way traditional fraud models expect. Credentials may be correct. Authentication may succeed. The anomaly lies in how the session behaves.

Examples that often surface at this stage include:

- Hesitation after successful login

- Repeated checking of account settings

- Short sessions that end without clear purpose

- Access from a device that technically matches but behaves differently

None of these events justify blocking on their own. Their value lies in establishing a baseline deviation that can be referenced later.

Customer support as a credibility amplifier

Support channels are where impersonation often accelerates. Here, fraudsters shift from technical access to social validation, using partial knowledge and plausible narratives to push for changes they could not make unaided.

Support teams rarely see the full behavioural picture. Without visibility into recent login patterns or device changes, these interactions can feel legitimate even when they are not.

New payee or beneficiary instructions as delayed-risk events

One of the most overlooked impersonation tactics is the quiet setup of future value extraction. Adding or modifying a payee does not immediately move money, which allows it to slip through controls designed to focus on instant loss.

These changes tend to:

- Appear operational rather than financial

- Occur days or weeks before funds are moved

- Be framed as “routine updates”

- Follow earlier identity or support interactions

Without lifecycle awareness, these events are easy to underweight until they are used.

Why impersonation must be treated as a lifecycle risk

Industry research consistently shows that impersonation is rarely confined to a single interaction. A meaningful share of identity fraud attempts involve someone convincingly claiming to be a legitimate user across multiple touchpoints, rather than relying on a single compromised credential. This reinforces a core reality: impersonation risk only becomes visible when identity, behaviour, and intent are evaluated together across the customer journey.

Model Design: Linking Identity, Device, Behaviour, and Transaction Intent

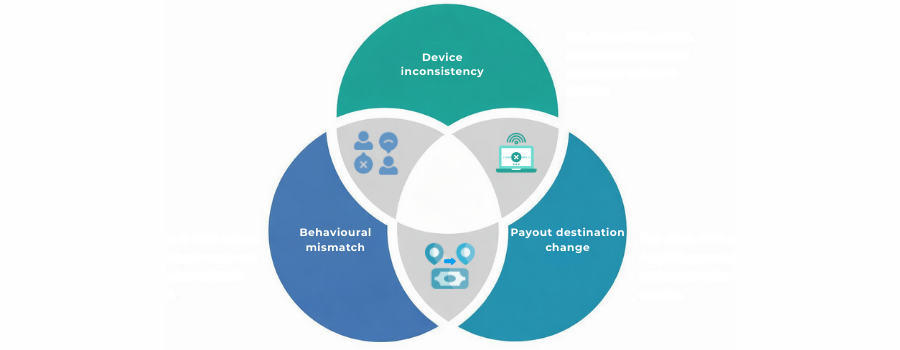

Impersonation fraud exposes a weakness in traditional fraud models: they are too event-focused. Checking whether a login succeeded, whether a device is recognised, or whether a transaction fits historical norms is no longer sufficient. Impersonation succeeds precisely because each of those checks can pass independently. Modern models therefore shift from scoring events to linking context.

At the core of this shift is the understanding that fraud is rarely a single action. It is a sequence of interactions that only becomes risky when those interactions are evaluated together.

Identity is the anchor, not the verdict

Strong identity signals still matter. Verified identity, long account tenure, and clean historical behaviour all reduce baseline risk. But in impersonation scenarios, identity confidence becomes the starting point, not the conclusion. Fraudsters often operate inside legitimate identities, borrowing credibility rather than trying to manufacture it.

This distinction is critical. A “known user” does not automatically mean a “trusted session”. Models that collapse identity trust and session trust into a single score tend to miss impersonation precisely because the identity looks correct while the behaviour does not.

Behaviour reveals intent before transactions do

Behavioural signals often surface impersonation earlier than financial activity. Fraudsters explore, test, and prepare before acting. These preparatory behaviours create subtle mismatches that static models struggle to interpret.

Common behavioural indicators include:

- Repeated visits to security or payout settings

- Hesitation before high-impact actions

- Switching between sections without completing tasks

- Activity bursts followed by inactivity

Behaviour does not prove fraud. It reveals direction. When behaviour begins to drift while identity remains constant, models gain an early signal that something is wrong.

Transaction intent as the final amplifier

Transaction intent is where impersonation risk crystallises. By the time a payout change, withdrawal, or new payee instruction is attempted, earlier signals either reinforce or weaken confidence. Importantly, intent is not scored uniformly. A purchase attempt and a payout change carry very different risk profiles, even when performed by the same identity.

Modern models therefore escalate risk dynamically, allowing earlier signals to carry more weight when intent shifts toward irreversible value movement.

Why linkage matters more than scoring

The defining capability of impersonation detection models is not more features, but better linkage. Single signals are noisy and easy to game. Linked signals create narratives that are harder to fake. When identity strength, device continuity, behavioural direction, and transaction intent align, confidence increases. When they diverge, impersonation risk becomes visible.

Industry research into identity fraud increasingly supports this view, showing that impersonation attempts rely on sustained credibility across multiple interactions rather than one-off anomalies. This reinforces why model design must prioritise relationships between signals, not isolated scores.

Signals That Expose Impersonation: When Behaviour Stops Matching the Identity

Impersonation is rarely exposed by a single red flag. It becomes visible when actions stop aligning with the identity’s long-established rhythm. What matters is not whether something is new, but whether it makes sense for that specific customer, at that specific moment, in that specific sequence.

When the device feels right but the session does not

A recognised device can still be in the wrong context. In impersonation cases, fraudsters often inherit technical familiarity but fail to reproduce behavioural continuity. This is why modern models downweight device recognition on its own and instead examine how that device is being used.

A session may technically pass every control while still feeling inconsistent:

- Settings are accessed before core actions

- Security pages are visited without a clear trigger

- Time spent per step no longer matches historical patterns

There is no single threshold here. The signal emerges only when compared against the identity’s own past behaviour.

Micro-signals that rarely matter alone

These indicators are weak in isolation, but powerful in accumulation:

- Session timing

- Cursor confidence

- Page revisits

- Order of actions

- Depth of exploration

- Pauses before irreversible steps

Individually, each could describe a distracted user. Together, they often describe someone rehearsing.

Behavioural mismatch appears before value extraction

One of the most important differences between impersonation and traditional fraud is timing. Behavioural drift almost always appears before money is touched. Fraudsters explore, confirm access, and prepare. That preparation phase is where detection has the highest leverage.

This is also why behavioural signals lose value quickly. If they are not captured and linked in near real time, they decay into noise.

Payout destination changes: the moment intent becomes explicit

When payout details change, impersonation risk crystallises. Earlier signals that felt ambiguous suddenly gain meaning. What matters is not the explanation, but the sequence. Destination changes that follow access recovery, support contact, or security exploration deserve far more weight than the same change in isolation.

Risk-based guidance on identity misuse and social engineering consistently emphasises this sequencing effect that intent is revealed through progression, not individual events. This principle is reinforced in the Financial Action Task Force’s risk-based approach guidance, which highlights the need to evaluate behaviour, identity, and intent together rather than as separate checks.

Tools That Stop Impersonation Without Breaking Trust

Impersonation defence fails when controls are either invisible or obstructive. The tools that work in 2026 are not blunt blockers; they are adaptive friction mechanisms that activate only when identity confidence and behavioural context diverge.

Risk-based step-up is not a single control

Step-up is no longer a binary escalation from “allow” to “challenge”. In impersonation scenarios, effective step-ups are incremental and context-aware. They respond to why risk has increased, not just that it has.

A step-up that follows a payout change should not look the same as one triggered by a login anomaly. Timing, channel, and customer history all matter. When applied correctly, step-up becomes a credibility test rather than a barrier confirming whether the person behind the session can maintain consistency under mild pressure.

Poorly designed step-ups expose impersonation controls. Well-designed ones surface it.

Session integrity checks (quiet, continuous, decisive)

These checks rarely announce themselves. They operate continuously in the background, building confidence or doubt without interrupting the user.

Common integrity signals assessed together:

- Input rhythm

- Session depth

- Interaction pacing

- Focus switching

- Environment stability

- Action sequencing

None of these prove identity. Their role is to confirm whether the session still belongs to the identity that started it.

Proof-of-ownership is most effective when delayed

Traditional identity proof often fails impersonation because it is applied too early or too aggressively. In modern workflows, proof-of-ownership is most powerful when used selectively, after risk has accumulated but before irreversible action occurs.

This might involve:

- Ownership confirmation tied to the specific change being requested

- Address or account verification triggered only for payout modifications

- Deferred checks that feel proportional rather than punitive

Used this way, proof becomes a filter for intent, not a wall against access.

Why proportional friction matters

Over-challenging legitimate users erodes trust and trains customers to expect disruption. Under-challenging impersonation allows fraud to hide inside familiarity. Regulatory guidance increasingly stresses that controls should be proportionate to risk and sensitive to context, particularly where social engineering and identity misuse are involved. This principle is reflected in UK expectations around systems and controls for preventing misuse while maintaining fair customer treatment.

Operational Flows: Blocking Impersonation Without Creating Customer Hostility

Impersonation fraud is rarely stopped by models alone. It is stopped by how organisations act on risk signals once they appear. The operational layer determines whether fraud controls quietly defuse threats or escalate into customer-facing incidents that damage trust, generate complaints, and overload support teams.

In 2026, effective operations are designed to absorb impersonation attempts without forcing customers to “prove themselves” unnecessarily.

The core challenge is sequencing. When friction appears too early, it feels arbitrary. When it appears too late, loss occurs. Operational flows therefore need to align with risk progression, not with channel ownership or internal team boundaries.

Customer communication as a control surface

The moment a user is contacted or not contacted matters. Fraudsters rely on silence, confusion, and urgency. Legitimate customers rely on clarity and predictability. Well-designed impersonation flows treat communication itself as a defensive layer.

What effective teams prioritise:

- Calm, neutral language

- No accusation framing

- Clear explanation of why an action is paused

- Time-bound next steps

What they actively avoid:

- Vague security warnings

- “Contact support immediately” panic triggers

- Repeated verification requests without context

Communication that explains process rather than suspicion dramatically reduces escalation and abandonment.

How operations decide when humans step in

Not every impersonation signal deserves analyst attention. Mature teams reserve human review for moments where judgement not pattern recognition is required.

Human intervention is typically triggered when:

- Risk signals escalate across channels

- Payout intent becomes explicit

- Automated step-ups fail silently

- Customer narratives conflict with session behaviour

- Value at risk exceeds predefined tolerance

These triggers are rarely identical across businesses. What matters is that they are explicit, documented, and auditable.

Why regulators care about operational handling

Regulatory expectations increasingly extend beyond detection into response. UK guidance on systems and controls emphasises that firms must not only identify misuse, but also respond in a way that is timely, proportionate, and fair to customers. This includes how firms communicate during security interventions and how consistently decisions are applied across channels.

Why Payout Risk Must Be Scored Differently From Purchase Risk

The most common modelling mistake in impersonation fraud is treating payouts as if they were simply another type of transaction. They are not. Purchase risk and payout risk behave differently, fail differently, and create loss in fundamentally different ways. Scoring them the same way hides impersonation until it is too late.

Purchase risk: reversible, distributed, expectation-heavy

Purchase risk is shaped by reversibility. Cards, wallets, and many payment rails are built around the assumption that mistakes and fraud can be corrected after the fact. Chargebacks, refunds, and customer complaints are all part of the expected lifecycle.

Because of this, purchase-side risk models tolerate uncertainty. They optimise for conversion, spread loss across portfolios, and rely on post-transaction remedies to correct errors. A false negative may be costly, but it is rarely terminal. Even a false positive can often be repaired through retries or alternative payment methods.

This tolerance is precisely what makes purchase-centric models dangerous when applied to payouts.

Payout risk: irreversible, concentrated, trust-loaded

Payout risk behaves differently because it removes value rather than requesting it.

- Irreversible

- Identity-anchored

- Silent failure

- No dispute path

- Treasury exposure

- Delayed visibility

- High confidence required

Once a payout is executed, recovery options collapse. There is no customer-initiated dispute, no scheme-level reversal, and often no immediate signal that something has gone wrong. Loss concentrates instantly, and accountability sits entirely with the merchant or platform.

Why identical scoring logic fails

When payout actions inherit purchase-risk thresholds, impersonation slips through precisely because the identity looks strong. Models trained to forgive uncertainty at checkout are poorly suited to moments where intent shifts from consumption to extraction.

In impersonation cases, the signals are often subtle but the consequences are absolute. Scoring systems that wait for “high confidence” based on transactional anomalies alone will miss the window where behavioural and contextual indicators are strongest.

This is why payout risk must be escalated earlier, with fewer signals required and higher weight placed on identity continuity and behavioural consistency.

Why regulators view payouts differently

Regulatory bodies increasingly treat payouts and value transfers as higher-impact events because of their finality. Guidance on payment finality and settlement risk consistently emphasises that once funds move, controls must already have been applied. This principle underpins why payout flows require stronger pre-authorisation confidence than purchase flows a distinction that modern impersonation models must reflect.

Conclusion

Impersonation fraud has reshaped how risk must be understood in 2026. It does not announce itself through obvious transaction anomalies or failed authentication attempts. It succeeds by blending into legitimacy, borrowing trust accumulated over time and exploiting gaps between identity, behaviour, and operational response. Treating it as a checkout-only problem leaves the most valuable moments supporting interactions, payout changes, beneficiary updates dangerously exposed.

The most effective defences do not rely on heavier controls or louder alerts. They rely on context. By linking identity confidence to behavioural continuity and intent progression, modern models detect impersonation earlier, when intervention is still possible and proportional. Separating payout risk from purchase risk, designing step-ups that test credibility rather than punish users, and aligning operations around risk progression all reduce loss without eroding trust.Ultimately, impersonation is not a single event to be blocked but a pattern to be interrupted. Merchants and platforms that treat it as a lifecycle risk instrumented across login, support, and payouts are better positioned to stop fraud quietly, protect customers, and preserve operational stability. In an environment where trust is increasingly fragile, recognising who is acting is no longer enough; understanding whether it still makes sense for them to act is what keeps payments and payouts safe.

FAQs

1. How is impersonation fraud different from account takeover (ATO)?

Impersonation fraud does not always involve taking over credentials or locking out the legitimate user. Instead, the fraudster operates as if they are the customer, often using valid access, partial information, or social engineering to trigger payouts or account changes without raising immediate alarms.

2. Why do traditional fraud models struggle to detect impersonation?

Most traditional models evaluate single events in isolation, such as a login or transaction. Impersonation relies on credibility across multiple interactions, meaning risk only becomes visible when identity, behaviour, and intent are evaluated together over time.

3. Which part of the customer journey is most vulnerable to impersonation?

Customer support and payout-related flows are particularly vulnerable. These channels rely heavily on trust and context, and impersonation attempts often succeed by exploiting gaps between technical signals and human decision-making.

4. Can strong identity verification alone prevent impersonation fraud?

No. Strong identity verification reduces baseline risk but does not guarantee that the person interacting with the system remains the legitimate user. Behavioural drift and intent shifts often reveal impersonation even when identity signals remain strong.

5. Why is payout fraud more dangerous than purchase fraud in impersonation cases?

Payouts are typically irreversible and lack dispute mechanisms. Once funds leave the platform, recovery options are limited. This makes payout actions the highest-impact moment in impersonation attacks and requires stricter, earlier risk escalation.

6. How can merchants reduce friction while still blocking impersonation?

By applying proportional, risk-based controls. Step-ups should be context-aware and triggered only when identity confidence and behaviour diverge, rather than applied uniformly across all users or actions.

7. What KPIs best indicate whether impersonation controls are working?

Metrics such as prevented payout loss, customer friction rate, and support-handled fraud attempts provide better insight than raw fraud rates. These KPIs show whether controls are stopping fraud without harming legitimate users.

8. Is impersonation fraud mainly a problem for high-risk merchants?

While high-risk merchants experience higher exposure, impersonation affects any platform handling payouts, stored balances, or sensitive account changes. Scale and trust, not just vertical, determine vulnerability.