Card testing has evolved into a form of automated reconnaissance rather than opportunistic fraud. In 2026, attackers no longer rely on manual trial and error. They deploy bots to probe authorisation flows at scale, mapping which combinations of card data, CVV, expiry, and merchant responses produce signals of life. The goal is not immediate theft, but intelligence identifying which cards, issuers, and merchants can be exploited later with confidence.

This shift changes how card testing must be defended. Blocking volume alone is not enough, and treating testing like standard fraud misses its purpose. Modern defence requires layered controls that suppress probing activity without leaking information through retries, decline behaviour, or inconsistent authentication handling. Merchants that fail to adapt do not just absorb operational noise; they risk issuer trust erosion, monitoring scrutiny, and downstream authorisation degradation.

- How Card Testing Attacks Work in 2025–26

- Layer 1: Bot Management and WAF Controls — Stopping Volume at the Edge

- Layer 2: Adaptive Throttling Models Risk-Based Limits, Not Static Rules

- Layer 3: Auth Hygiene Preventing Signal Leakage at the Moment of Decision

- Routing Reality: How Card Testing Affects Issuer Trust and Acquirer Monitoring

- Merchant UX: Blocking Attacker Retries Without Breaking Legitimate Recovery

- KPIs That Reveal Card Testing Before Fraud Appears

- Conclusion

- FAQs

How Card Testing Attacks Work in 2025–26

Card testing in 2025–26 no longer looks like crude fraud attempts. It behaves more like automated reconnaissance. Attackers deploy bots to probe merchant authorisation flows, not to steal value immediately, but to learn how systems respond under pressure. Each request is a question, and each response becomes a data point.

What merchants often miss is that their checkout and authorisation behaviour acts as a signal source. Response timing, decline handling, retry tolerance, and authentication sequencing all reveal information. Issuers may never see the early probes as fraud, but they do see the patterns merchants generate when those probes pass through. Over time, this erodes trust long before any confirmed fraud occurs.

What attackers are actually measuring

Attackers are not guessing blindly. They are measuring system behaviour with intent to adapt.

- Response latency

- Decline consistency

- Retry tolerance

- Velocity ceilings

- Authentication sequencing

These signals allow bots to infer which card data combinations are live, which merchants leak information through error handling, and which routes are safest for later monetisation. Even failed attempts are useful if they produce distinguishable responses.

Once probes begin to show signs of life, attackers shift tactics. They cluster results, grouping cards, BINs, devices, or flows that behave similarly. Traffic patterns evolve dynamically: retries are spaced, volumes redistributed, and payloads adjusted to remain just below static thresholds. Traditional rate limits struggle here because the attack surface is no longer linear or noisy.

Why success clustering matters

Success clustering is what turns testing into scalable exploitation. When bots identify pockets of permissive behaviour, they can return later with confidence, using higher-value fraud techniques against merchants and issuers that have already been mapped. This is why card testing causes disproportionate downstream damage compared to the immediate losses it creates.

Industry analysis of modern card testing highlights this shift clearly: testing is less about draining cards and more about learning which systems are predictable, tolerant, or slow to react. That insight is what fuels later fraud waves, issuer scrutiny, and monitoring pressure across the ecosystem.

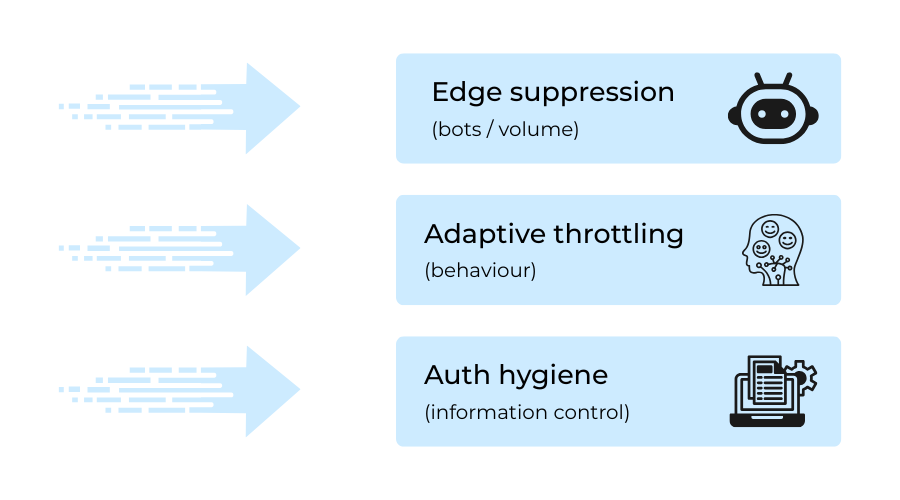

Once card testing is understood as reconnaissance rather than isolated fraud attempts, the limits of single-point controls become obvious. No individual rule, tool, or threshold can reliably suppress probing that adapts in real time. What works instead is layered containment controls that reduce volume, absorb learning attempts, and prevent signal leakage even when some requests inevitably pass through.

The next three sections examine this defence as a layered approach. Each layer addresses a distinct aspect of card testing behaviour, from traffic volume to retry logic and signal leakage, reflecting how modern testing activity adapts across different parts of the payment flow.

Layer 1: Bot Management and WAF Controls — Stopping Volume at the Edge

Card testing almost always begins as a volume problem. Before attackers learn anything meaningful about authorisation logic, they need enough requests to observe patterns. That makes the edge where traffic first arrives the only place merchants can cheaply and decisively suppress noise before it turns into signal. Bot management and WAF controls exist for this reason: not to detect fraud, but to prevent reconnaissance from scaling.

At this layer, success is measured in reduction, not resolution. The goal is to ensure that obvious automation never reaches application logic where it can start learning.

What edge controls are actually good at

- Request floods

- Headless browsers

- Scripted retries

- IP churn

- Payload reuse

- Non-human timing

These patterns are not subtle, and they do not need deep context to identify. Well-tuned edge controls are effective precisely because they operate without interpretation. They reduce surface area, lower baseline noise, and buy time for downstream systems.

Where edge controls fall short

The limitation of Layer 1 is also its defining characteristic: it has no memory. Once attackers adapt rotating devices, slowing velocity, randomising payloads, edge controls lose their advantage. Smart bots are designed to look boring. They trade speed for persistence, slipping past static signatures and simple rate limits.

This is why merchants often experience a false sense of security. Traffic volume drops, dashboards look clean, and yet issuer monitoring flags begin to rise. The learning has not stopped; it has simply moved inward.

Card testing analysis from large issuers consistently shows that while edge suppression reduces obvious abuse, it does not prevent adaptive probing from extracting insight when authorisation behaviour remains predictable. This is why bot management is a prerequisite, not a solution.

Why Layer 1 must stay limited

Layer 1 is intentionally blunt. It should never be overloaded with logic it cannot support. The moment edge controls are expected to distinguish between legitimate retries and intelligent probing, they become brittle. Their role is containment, not judgement.

Once raw volume is suppressed, the attack surface shifts. What remains is lower-frequency, higher-quality traffic that requires adaptive controls to manage. That transition is where static limits fail and where the next layer becomes critical.

Layer 2: Adaptive Throttling Models Risk-Based Limits, Not Static Rules

Static rate limits fail for the same reason card testing succeeds: predictability. Fixed thresholds tell attackers exactly how far they can go before resistance appears. Once that line is mapped, probing activity simply reorganises itself to stay just below it. In 2026, effective throttling is no longer about setting ceilings; it is about continuously reshaping the surface attackers are trying to learn from.

Adaptive throttling starts from a different assumption. It treats retry behaviour, pacing, and persistence as signals in their own right, rather than noise to be tolerated. The objective is not to block every request, but to remove the feedback loops that make reconnaissance efficient.

Static limits create feedback

When limits are fixed, they become instructional. Bots learn how many attempts are tolerated, how quickly retries can occur, and which failures are “safe” to repeat. Over time, this creates a stable testing corridor where attackers can operate indefinitely without triggering alerts, while issuers and acquirers quietly absorb the downstream effects.

Adaptive models disrupt this learning by making outcomes inconsistent for suspicious patterns, even when individual requests appear legitimate.

What adaptive throttling actually responds to

- Retry spacing

- Decline clustering

- Behavioural persistence

- Session entropy

- Confidence after failure

- Payload mutation

These inputs are not evaluated in isolation. They are interpreted together, over time, to decide whether friction should increase, decrease, or shift form. The same user may experience no throttling at all in one session and increasing delay in another, depending entirely on context.

Why this is not “rate limiting 2.0”

Adaptive throttling is often misunderstood as more aggressive blocking. In practice, it is usually quieter. Legitimate customers retry for understandable reasons: network errors, authentication lapses, or momentary interruptions. Their behaviour tends to stabilise quickly once the issue is resolved.

Testing bots do the opposite. They persist, adjust, and probe. Adaptive throttling exploits that difference by stretching time rather than slamming doors. Delays grow unevenly. Responses become less informative. Learning slows to the point where testing is no longer economical.

A legitimate customer notices a pause. An attacker loses a feedback signal.

In practice, this creates two very different paths through the same system. Genuine users recover access with minimal friction, while automated probing collapses under its own persistence. Issuer-facing metrics improve not because traffic disappears, but because it stops behaving like reconnaissance.

Layer 3: Auth Hygiene Preventing Signal Leakage at the Moment of Decision

If card testing is reconnaissance, authorisation handling is the map. Attackers learn far more from how a transaction fails than from whether it fails. Every decline, retry allowance, and conditional response teaches something about where the boundaries are. In 2026, the most sophisticated defences do not focus on maximising declines; they focus on minimising what those declines reveal.

Auth hygiene is therefore less about strength and more about discipline. It is the practice of ensuring that authorisation behaviour is predictable to legitimate users and uninformative to automated probing.

Where auth responses leak information

Signal leakage rarely comes from one dramatic mistake. It comes from small inconsistencies that accumulate over time.

- Decline reason specificity

- CVV versus AVS sequencing

- Retry tolerance after partial checks

- Inconsistent soft declines

- Channel-dependent messaging

- Timing asymmetry between outcomes

Each of these elements may seem harmless in isolation. Together, they allow attackers to infer which fields are being checked, in what order, and how close a request was to approval.

Why retries are the real teacher

A single decline tells an attacker very little. A retry tells them everything. When systems allow repeated attempts with slight variations, they effectively confirm hypotheses: which values matter, which checks are enforced, and which failures are recoverable.

This is why permissive retry logic is more dangerous than permissive approvals. A clean, consistent failure ends learning. A “nearly successful” failure invites refinement. In high-volume environments, that refinement happens faster than any rule update can keep up with.

Auth hygiene treats retries as part of the decision, not an afterthought. Limiting what changes between attempts and how those changes are reflected in responses — is often more effective than tightening individual checks.

Hygiene is about predictability, not harshness

Well-designed auth handling does not feel aggressive to real customers. It feels boring. Responses are consistent. Outcomes are stable. Behaviour that is allowed once is allowed again, and behaviour that is blocked stays blocked.

Characteristics of hygienic auth handling include:

- Stable response patterns across attempts

- Uniform decline handling across channels

- Minimal variance in timing and messaging

When these conditions are met, legitimate users recover quickly and move on. Attackers, on the other hand, lose the ability to learn. The system stops teaching.

Why Layer 3 completes the stack

Layer 1 reduces noise. Layer 2 slows adaptation. Layer 3 ensures that whatever remains cannot extract insight. Auth hygiene is invisible when it works, which is why it is often undervalued. Yet it is this final layer that protects issuer trust, preserves acquirer confidence, and prevents reconnaissance from turning into sustained abuse.

Once authorisation stops leaking information, card testing becomes inefficient. And when it becomes inefficient, it moves elsewhere.

Routing Reality: How Card Testing Affects Issuer Trust and Acquirer Monitoring

From an issuer’s point of view, card testing does not exist as a labelled threat. What they see instead are patterns: clusters of low-value authorisation failures, repeated CVV mismatches, and unusual retry behaviour across merchants. Individually, these signals look unremarkable. Collectively, they reshape how trust is assigned. Once a merchant’s traffic begins to look noisy or exploratory, intent becomes irrelevant. Risk scoring adjusts automatically.

This is why card testing is so dangerous even when direct fraud losses remain low. Issuers do not wait for confirmed abuse. They react to uncertainty. When authorisation streams start to resemble probing rather than commerce, approval tolerance tightens. This happens silently and incrementally, long before merchants see chargebacks or alerts.

From the issuer’s perspective

Issuers evaluate behaviour at scale. They do not distinguish between “testing” and “failed payments”; they measure how often credentials are presented unsuccessfully, how retries cluster, and whether patterns repeat across cards or time windows. When failure density increases, confidence decays.

Crucially, this decay is sticky. Once a merchant’s traffic profile shifts, subsequent legitimate transactions are evaluated through a colder lens. Customers experience declines that feel random, even though the root cause is systemic rather than individual.

How acquirers respond

Acquirers sit between merchant behaviour and issuer reaction, and their incentives are aligned with stability. When testing activity persists, acquirers rarely intervene loudly. Instead, responses tend to be subtle and commercial.

Common outcomes include:

- Monitoring programme flags

- Routing restrictions

- Increased scrutiny thresholds

- Soft volume caps

- Silent risk repricing

These measures are designed to reduce exposure without triggering confrontation. For merchants, they often manifest as unexplained approval deterioration or constrained growth rather than explicit warnings.

Why this matters to merchants

Routing degradation usually appears before fraud losses. Approval rates fall gradually. Certain issuers become harder to reach. Payment performance worsens in ways that are difficult to diagnose from dashboards alone. By the time card testing is identified as the cause, issuer trust has already been recalibrated.

This is why defending against testing is not just about blocking bots. It is about preserving tolerance. Merchants that suppress reconnaissance early maintain routing flexibility, sustain issuer confidence, and avoid the slow erosion that turns manageable noise into commercial friction.

Merchant UX: Blocking Attacker Retries Without Breaking Legitimate Recovery

Attackers and customers retry for entirely different reasons. An attacker retries to extract information. A customer retries to complete a task. When systems treat both behaviours as equivalent, they either leak signal to attackers or punish legitimate users unnecessarily. Merchant UX is where that distinction becomes visible.

This is why retry handling is not just a fraud problem. It is a design problem. Well-designed recovery flows make it easier for real customers to succeed while making automated probing inefficient and unrewarding.

Attackers retry to learn

Automated testing relies on repetition. Bots adjust one variable at a time, measure outcomes, and repeat until boundaries become clear. Speed, consistency, and persistence are advantages. Friction is a cost to be minimised.

Customers retry to succeed

Legitimate users behave differently. They pause, reconsider, switch devices or payment methods, and often abandon attempts altogether if friction persists. Their goal is completion, not optimisation. These differences are subtle but reliable when viewed across sessions rather than single events.

UX signals that attackers can’t fake

Certain behaviours consistently distinguish recovery from reconnaissance, especially when observed together rather than in isolation.

- Hesitation before retry

- Channel switching

- Payment method changes

- Support engagement

- Session abandonment patterns

- Behavioural cooling-off

- Contextual consistency

Attackers can simulate volume and variation, but they struggle to replicate hesitation, uncertainty, and disengagement. UX that allows these signals to surface naturally gives risk systems more room to respond intelligently.

Designing recovery flows around these signals does not require harsher controls. It requires restraint. Error messages should guide users without revealing thresholds. Retry options should exist, but not invite experimentation. Time-based friction short pauses, session resets, or delayed availability often deters bots more effectively than outright blocks.

Designing recovery paths that don’t teach

The most dangerous recovery experiences are the most helpful ones. Explicit guidance on what went wrong, unlimited retries, and immediate feedback loops accelerate attacker learning. In contrast, opaque but fair recovery paths slow probing while remaining usable for genuine customers.

Effective recovery design accepts that some legitimate users will take longer to succeed. That trade-off is intentional. Customers recover through patience and reassurance. Attackers disengage when learning becomes expensive.

When UX is treated as a risk surface rather than a conversion afterthought, it becomes a quiet control layer. One that improves trust, reduces noise, and preserves long-term payment performance.

KPIs That Reveal Card Testing Before Fraud Appears

Card testing rarely announces itself through chargebacks or confirmed fraud. By the time those metrics move, issuer trust has already shifted. The most useful indicators sit earlier in the lifecycle, where behaviour begins to drift but outcomes still look harmless. These KPIs are designed to surface reconnaissance patterns before they translate into routing damage or approval decay.

Rather than tracking success or failure in isolation, they focus on shape, concentration, and persistence.

Authorisation failure anomaly alerts

Raw decline rates are a blunt instrument. What matters is whether failures behave differently from historical norms for the same merchant, route, or time window. An anomaly alert is triggered not by volume alone, but by deviation.

Signals that typically matter:

- Sudden clustering of low-value failures

- Repeated CVV or expiry mismatches across short intervals

- Failure spikes isolated to specific BIN ranges

- Elevated retries without corresponding approvals

These patterns often emerge during reconnaissance phases, when attackers are mapping tolerance rather than attempting to transact meaningfully. Monitoring failure shape instead of totals allows teams to intervene earlier, when suppression is still cheap.

Request entropy

Entropy measures how predictable traffic is. Legitimate payment activity contains natural randomness: different amounts, devices, timings, and user paths. Card testing does the opposite. It reduces variance to isolate signals.

Low request entropy typically shows up as:

- Repeated amounts

- Narrow timing bands

- Minimal payload variation

- Consistent sequencing across attempts

As entropy drops, learning efficiency rises. Tracking this metric helps teams identify when traffic is becoming too consistent to represent genuine commerce, even if absolute volumes remain modest.

Device and IP reuse rate

High reuse rates are not inherently malicious. What matters is reuse combined with failure. When the same devices, IPs, or network characteristics appear repeatedly in unsuccessful authorisation flows, it suggests iterative probing rather than customer difficulty.

Warning signs include:

- Devices associated with many failed cards

- IPs that persist across rotated credentials

- Reuse patterns that survive throttling or edge suppression

Unlike simple velocity checks, reuse metrics expose persistence. They reveal whether traffic is adapting around controls or disengaging as legitimate users typically do.

Why these KPIs work together

Individually, each metric can be noisy. Together, they tell a coherent story. Failure anomalies indicate where behaviour has changed. Entropy shows how structured that behaviour is. Reuse rates reveal whether the actor is learning or giving up.

This combination allows teams to distinguish between operational issues, customer friction, and deliberate reconnaissance without waiting for financial loss or scheme intervention to confirm suspicion.

Conclusion

Card testing in 2026 is no longer a blunt attack that can be stopped with a single rule or threshold. It is a learning exercise carried out at scale, designed to extract insight from systems that respond too predictably. Merchants that treat it as a conventional fraud problem often focus on the wrong outcomes blocking transactions rather than protecting trust.

What consistently works is layered containment. Edge controls reduce noise. Adaptive throttling disrupts learning. Auth hygiene prevents signal leakage. UX design differentiates recovery from reconnaissance. None of these layers is sufficient on its own, but together they reshape the economics of testing until it no longer makes sense for attackers to persist.

The most important shift is perspective. Card testing is not primarily about financial loss; it is about tolerance. Issuer confidence, acquirer appetite, and routing quality are all shaped long before chargebacks appear. Merchants that defend early preserve those relationships and maintain approval performance, even under pressure.

In an environment where automated probing is constant, resilience comes from design, not reaction. Multilayered prevention does not just stop card testing it quietly ensures that payment systems remain boring, predictable, and trusted.

FAQs

1. What is card testing and why is it still a problem in 2026?

Card testing remains a problem because it has evolved into automated reconnaissance rather than simple fraud attempts. Attackers use bots to learn how merchants, issuers, and acquirers respond to failed authorisations, enabling more effective fraud later even if immediate losses are low.

2. Why don’t traditional fraud rules stop card testing effectively?

Traditional rules focus on transaction-level outcomes like approvals or declines. Card testing exploits predictability across retries, timing, and responses, allowing attackers to learn system behaviour without triggering obvious fraud thresholds.

3. How does card testing affect merchants even when fraud losses are minimal?

The primary impact is on issuer trust and acquirer tolerance. Persistent testing activity increases authorisation noise, which can lead to routing degradation, lower approval rates, and increased monitoring long before chargebacks appear.

4. What role does bot management actually play in stopping card testing?

Bot management is effective at suppressing obvious automation and high-volume probing at the edge. However, it does not stop adaptive testing on its own and should be treated as a containment layer rather than a complete defence.

5. Why is adaptive throttling more effective than static rate limits?

Static limits teach attackers where the boundaries are. Adaptive throttling changes outcomes based on behaviour over time, slowing learning and making probing inefficient without blocking legitimate customers unnecessarily.

6. What does “auth hygiene” mean in the context of card testing?

Auth hygiene refers to controlling how much information authorisation responses reveal. Consistent decline handling, controlled retries, and uniform messaging prevent attackers from learning which checks are enforced or how close a transaction was to approval.

7. How can merchants protect customer experience while limiting retries?

By designing recovery flows that favour human behaviour, such as hesitation, channel switching, and disengagement. These patterns are difficult for bots to fake and allow genuine customers to recover without enabling automated probing.