For years, card testing and enumeration lived in an uncomfortable grey zone. Everyone knew it was bad. Everyone dealt with it. But it was still treated as background noise, an operational headache for fraud teams rather than something with real strategic consequences. If the attacker didn’t monetise and chargebacks stayed low, the damage felt containable.

That assumption no longer holds.

By 2026, Visa’s posture has shifted in a way that many merchants and more than a few PSPs are still catching up with. Enumeration, especially BIN-range card testing, is no longer judged purely on fraud losses. It’s judged on behaviour. Volume. Patterns. Network impact. And crucially, it now feeds directly into scheme-level monitoring under Visa’s Acquirer Monitoring Program (VAMP).

This is where the risk profile changes. Merchants can do everything right in the traditional sense: low chargebacks, fast response times, minimal confirmed fraud and still find themselves under pressure. Not because money was lost, but because their checkout became a testing surface that created measurable risk upstream.This blog is about that shift. Why BIN-range testing now carries programme-level consequences, how Visa can see enumeration in ways individual merchants cannot, and why high-risk businesses feel the impact first. If enumeration is still sitting in your organisation as a fraud ops issue, 2026 is the year that framing starts to hurt.

- What Visa Now Means by Enumeration

- VAMP Changes the Risk Conversation Completely

- Why BIN-Range Testing Is Especially Dangerous Under VAMP

- Why Quiet Enumeration Is No Longer Quiet

- How Scheme-Program Risk Actually Shows Up

- Why High-Risk Merchants Feel This First

- Common Merchant Blind Spots That Make Enumeration Worse

- Common Merchant Blind Spots That Make Enumeration Worse

- Conclusion

- FAQs

What Visa Now Means by Enumeration

When Visa talks about enumeration, it is not using the term loosely. It’s referring to a very specific class of behaviour that turns the payment network itself into a validation engine. In simple terms, enumeration is any attempt to systematically test card credentials whether that’s full PANs, partial PANs, expiry dates, CVVs, or combinations of the three to work out which cards are real and usable.

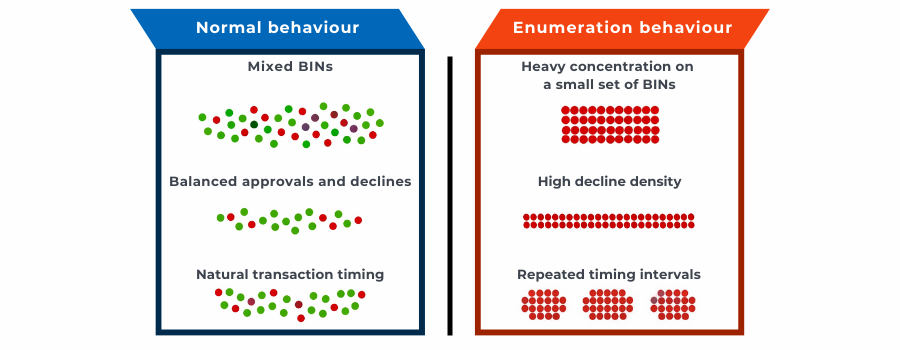

What often gets missed is that Visa’s definition is behavioural, not outcome-based. Enumeration does not require successful fraud. It does not require chargebacks. It does not even require a completed purchase. What matters is the pattern: repeated authorisation attempts that are clearly designed to learn something about card validity rather than to complete a genuine transaction.

BIN-range testing sits squarely inside that definition. Instead of attacking one known card, the attacker works horizontally across a BIN or IIN range, probing thousands of permutations. Most attempts fail. That’s the point. Each decline teaches the attacker something, and each attempt creates network noise that Visa can measure.

Visa has been explicit about this in its own guidance. Enumeration and account testing are framed as ecosystem threats that merchants and acquirers are expected to actively prevent, not merely react to Visa guidance on enumeration attacks. The language matters here. This is not advice. It’s an expectation.

Another important nuance is that enumeration is not limited to obvious “micro-amount” attacks anymore. In practice, Visa sees a mix of:

- Normal-looking low-ticket purchases,

- Distributed attempts spread over time and endpoints.

That evolution is exactly why relying on simple thresholds or that looks weird rules no longer holds up. Enumeration blends into legitimate traffic unless you are explicitly looking for learning behaviour, not just fraud outcomes.

The key takeaway for 2026 is this: if your checkout can be used to test cards at scale, Visa will classify that as enumeration activity whether or not your business loses money. And once it is classified that way, it stops being a local fraud issue and starts becoming a scheme-facing risk signal.

VAMP Changes the Risk Conversation Completely

Before VAMP, most merchants thought about scheme risk in fairly narrow terms. Chargebacks crept up, fraud ratios crossed a line, and then programmes kicked in. Enumeration sat off to the side unpleasant, noisy, but rarely decisive on its own.

VAMP changes that framing.

Visa’s Acquirer Monitoring Program brings fraud, disputes, and enumeration into the same risk conversation. That matters because it removes the old safety valve where “nothing bad actually happened” could be used as a defence. Under VAMP, Visa is less interested in whether an attack succeeded and more interested in whether your traffic patterns indicate that the network is being misused through your merchant or acquirer relationship Visa Acquirer Monitoring Program overview.

This is a subtle but important shift. VAMP doesn’t require a spike in losses to justify attention. It relies on measurable indicators abnormal authorisation behaviour, persistent enumeration signals, and patterns that suggest a merchant environment is attractive to attackers. Once those signals are present, the conversation moves upstream quickly.

For acquirers, VAMP creates a different kind of accountability. They are no longer reacting only to downstream damage. They are expected to demonstrate that they can identify and suppress behaviour that threatens network integrity, even if it hasn’t yet produced chargebacks. That expectation naturally flows down to merchants, especially those already classed as higher risk.

What makes this uncomfortable for many businesses is that enumeration doesn’t feel like a failure in the traditional sense. Controls might be working. Transactions are declining. Fraud teams are blocking what they can see. Yet from Visa’s perspective, the presence of sustained testing traffic still represents exposure. The network is being used as a learning tool, and VAMP is designed to discourage exactly that.

In practical terms, VAMP compresses timelines. Issues that once lingered quietly now escalate faster. Questions arrive earlier. Remediation expectations become clearer and less forgiving. Enumeration is no longer something you clean up once it becomes obvious. Under VAMP, the expectation is that it shouldn’t be visible at scale in the first place.

That’s the crux of the change. VAMP turns enumeration from a background fraud signal into a programme-relevant risk indicator. And once it sits in that category, merchants lose the luxury of treating card testing as just one of those things.

Why BIN-Range Testing Is Especially Dangerous Under VAMP

BIN-range testing is dangerous under VAMP not because it is clever, but because it is structurally loud. Even when attackers try to stay subtle, the behaviour it creates is exactly the kind of thing a scheme can measure at scale.

The problem starts with how BIN-range testing works in practice. Instead of targeting one stolen card, attackers probe horizontally across a BIN or IIN range. Most attempts are expected to fail. That failure is the signal. Each decline narrows the search space, and each attempt adds another data point to the network’s view of what is happening.

From a merchant’s perspective, this often feels manageable. Declines go up. Fraud teams see noise. Nothing settles. No chargebacks arrive. It feels contained.

From Visa’s perspective, it looks very different.

BIN-range testing produces recognisable network patterns that don’t require successful fraud to stand out. It creates traffic that is:

- Disproportionately skewed toward specific BINs,

- Heavy on CVV and expiry mismatches,

- Clustered in short bursts or distributed in unnatural low-and-slow rhythms.

Under VAMP, those patterns matter more than outcomes. The scheme is not asking, Did the attacker win? It’s asking, Is this merchant environment being used to learn about cards?

This is why BIN-range testing carries outsized programme risk:

- Repeated failures still consume network and issuer resources

- Behaviour is attributable even when value never moves

What makes this especially uncomfortable is that good defensive behaviour doesn’t always reduce visibility. Declining everything quickly might stop losses, but it doesn’t erase the pattern. In some cases, aggressive declines actually make the testing behaviour cleaner and easier to classify at network level.

Another overlooked factor is correlation. BIN-range testing rarely targets a single merchant in isolation. Attackers reuse scripts and logic across multiple entry points. That means Visa can observe similar behaviour appearing across merchants and acquirers at the same time, tied together by BIN activity rather than merchant IDs. At that point, individual explanations matter less than aggregate evidence.

Under VAMP, that aggregate evidence feeds directly into programme judgement. Enumeration that once felt like background noise now looks like a persistent misuse signal. And because BIN-range testing scales horizontally, it reaches that threshold faster than most merchants expect.

The uncomfortable truth is this: BIN-range testing doesn’t need to be successful to be damaging. It only needs to be visible. Under VAMP, visibility is enough to turn a technical nuisance into a scheme-level problem.

Why Quiet Enumeration Is No Longer Quiet

For a long time, there was an unspoken belief in fraud teams: if you rate-limit hard enough, slow things down, and keep individual attempts small, enumeration will stay below the radar. It might be annoying, but it won’t escalate.

That belief is now outdated. The core problem is that “quiet” only exists at merchant level. Visa does not look at enumeration one merchant at a time. It looks at it across the network. What appears as low-level noise in your logs can form a very clear signal once it’s aggregated across merchants, acquirers, and issuers.

This is where many teams get caught out. They’re optimising controls for local visibility IP velocity, device counts, per-merchant thresholds while Visa is correlating behaviour horizontally. Same BIN ranges. Similar decline patterns. Repeated CVV and expiry permutations. Consistent timing signatures. Spread out, but unmistakably related.

Visa has been explicit about this capability. In its Payment Ecosystem Risk & Control (PERC) reporting, Visa describes how it uses network-level analytics, including Visa Account Attack Intelligence (VAAI), to detect enumeration and account testing patterns and alert affected parties. That detection does not depend on a single merchant seeing enough activity to panic Visa PERC Biannual Threats Report.

This changes the risk calculus in a subtle but important way. A merchant can believe they are handling enumeration responsibly, blocking aggressively, declining everything, seeing no losses and still contributing to a recognisable attack pattern at scheme level. In fact, highly consistent declines can sometimes make correlation easier, not harder.

There’s also a timing issue. Enumeration used to escalate slowly. Now it compresses. Network-level detection shortens the gap between “background noise” and “programme conversation”. By the time a merchant realises enumeration is persistent, the acquirer may already be answering questions.

The takeaway for 2026 is uncomfortable but clear. If your strategy relies on enumeration staying small enough to ignore, it’s built on an assumption that no longer holds. Quiet enumeration is only quiet in isolation. At network scale, it’s just another measurable signal and under VAMP, measurable signals don’t stay benign for long.

How Scheme-Program Risk Actually Shows Up

One of the reasons enumeration risk is still underestimated is that scheme-programme pressure rarely arrives with a single, dramatic event. There’s no obvious way you’ve failed. Instead, it shows up as a sequence of signals and constraints that tighten over time often before a merchant realises what triggered them.

This is where VAMP changes the experience from theoretical to very real.

What Acquirers Start Doing Differently

When enumeration becomes visible at scheme level, acquirers are usually the first to feel the heat. And when acquirers feel pressure, they move quickly because the programme relationship sits with them.

In practice, that often looks like:

- Earlier and more detailed traffic reviews

- Requests for evidence that enumeration controls are in place

- Reduced tolerance for “expected noise” explanations

What’s changed is the burden of proof. Acquirers are no longer satisfied with blocking it when we see it. They want to understand why your environment is attractive for testing in the first place and what you’re doing to make it unattractive.

That scrutiny tends to escalate faster for high-risk MCCs, simply because acquirers already expect tighter control there.

What Merchants Experience on the Ground

From the merchant side, scheme-programme risk doesn’t usually feel like a fraud incident. It feels like pressure.

Limits tighten. Conversations change tone. Controls that were previously optional suddenly become mandatory. In some cases, merchants are asked to implement measures that have nothing to do with losses and everything to do with behavioural signals.

Typical symptoms include:

- Requests for rapid changes to checkout or auth flows

- Increased holds, reserves, or conditional processing

- Explicit warnings about pattern risk rather than fraud loss

What makes this frustrating is that many of these merchants haven’t lost money. Cards didn’t get charged. Customers didn’t complain. Chargebacks stayed flat. Yet the environment is still judged as risky because it allowed the network to be used as a testing surface.

Why This Feels Sudden (But Isn’t)

Scheme-programme exposure often feels abrupt because merchants don’t see the network-level view. Enumeration doesn’t escalate in isolation. It accumulates.

By the time an acquirer raises the issue, Visa has usually already seen:

- Repeated patterns tied to specific BIN ranges

- Similar behaviour across multiple merchants

- Persistence over time, even if volume per merchant is modest

From that vantage point, the question isn’t did this merchant fail? Does this environment contribute to ecosystem risk?

That distinction matters. Under VAMP, scheme-programme risk is less about punishment and more about forcing earlier correction. The goal is to shut down testing surfaces before they become systemic.

For merchants, the lesson is uncomfortable but useful. If scheme-programme pressure feels like it came out of nowhere, it’s usually because enumeration was visible somewhere else first. By the time it reaches you, the decision window is already narrower than it looks.

Why High-Risk Merchants Feel This First

High-risk merchants don’t attract enumeration because they’re careless. They feel the impact first because they sit closer to every threshold that matters operationally, commercially, and politically within the payments stack.

Start with baseline metrics. High-risk businesses already operate with higher natural decline rates, more issuer scrutiny, and tighter acquirer oversight. When BIN-range testing appears, even briefly, it stacks on top of an already sensitive profile. What might look like a small spike for a low-risk retailer can look like a material behavioural shift for a high-risk merchant.

There’s also the question of attractiveness. Attackers don’t choose targets at random. They look for environments where:

- Retries are predictable

- Controls are visible only after several attempts

High-risk verticals digital services, gaming, FX, adult, subscriptions often need smoother checkout flows to convert. That smoothness, if not carefully designed, can unintentionally create ideal testing surfaces.

Then there’s acquirer tolerance. High-risk merchants are already “known quantities” within acquirer risk teams. When enumeration appears, the benefit of the doubt is shorter. Acquirers are quicker to intervene because the downside of waiting feels larger not just for fraud loss, but for scheme perception.

What makes this particularly frustrating is that high-risk merchants are often doing more than their low-risk peers. Dedicated fraud teams. Sophisticated tooling. Fast response times. None of that changes the fact that scheme-level risk is judged on patterns, not effort. Under VAMP, intent matters less than observable behaviour.

The compounding effect is what really hurts. Enumeration decreases. Higher declines damage issuer confidence. Damaged confidence tightens acceptance. Tightened acceptance pressures conversion. And all of it happens without a single successful fraudulent transaction.

That’s why high-risk merchants feel VAMP-driven enumeration pressure first. Not because they’re weaker but because they’re operating in an environment where there’s less room for noise. In 2026, being high-risk doesn’t just mean managing fraud better. It means ensuring your payments stack doesn’t accidentally become a measurement point for the scheme.

Common Merchant Blind Spots That Make Enumeration Worse

Most merchants don’t invite enumeration. But a handful of design and operational blind spots make card testing far easier than teams realise even in environments that look well controlled on paper.

One of the biggest issues is retrying logic that’s too polite. Many checkout flows are built to help genuine customers recover from mistakes. Soft declines trigger retries. Error messages are clear. Alternative attempts are encouraged. For real users, that’s good UX. For attackers, it’s a free signal. Each retry confirms what didn’t work and narrows the search space.

Another blind spot is overconfidence in point controls. Rate limiting at the IP level, basic velocity rules, or CAPTCHA on the first attempt all help but they don’t address distributed testing. Enumeration today is rarely noisy in one place. It’s spread across devices, sessions, and sometimes merchants. Controls that only look “locally” miss the pattern entirely.

Refunds and voids are another quiet leak. Well-intentioned clarity around refunds, immediate status updates, explicit confirmations, predictable timelines can inadvertently confirm state. When a system responds differently to a valid versus invalid credential, attackers notice. Over time, those differences become part of the testing logic.

There’s also a structural assumption that acquirers will absorb the risk. Some merchants believe that if enumeration is widespread, the acquirer or network will filter it out upstream. Under VAMP, that assumption is backwards. Acquirers are now expected to show that they are pushing controls downward, not absorbing noise on behalf of merchants.

Finally, many teams underestimate how quickly patterns become visible outside their own dashboards. Fraud teams often ask, “Is this enough to worry about?” The uncomfortable answer is that by the time it feels serious locally, it may already be obvious at network level.

None of these blind spots indicate negligence. They indicate systems optimised for conversion and support, not for hostility toward learning attacks.

In 2026, that distinction matters. Enumeration doesn’t exploit one big weakness. It exploits lots of small, reasonable decisions that add up to a usable testing surface.

Common Merchant Blind Spots That Make Enumeration Worse

Most merchants don’t invite enumeration. But a handful of design and operational blind spots make card testing far easier than teams realise even in environments that look well controlled on paper.

One of the biggest issues is retrying logic that’s too polite. Many checkout flows are built to help genuine customers recover from mistakes. Soft declines trigger retries. Error messages are clear. Alternative attempts are encouraged. For real users, that’s good UX. For attackers, it’s a free signal. Each retry confirms what didn’t work and narrows the search space.

Another blind spot is overconfidence in point controls. Rate limiting at the IP level, basic velocity rules, or CAPTCHA on the first attempt all help but they don’t address distributed testing. Enumeration today is rarely noisy in one place. It’s spread across devices, sessions, and sometimes merchants. Controls that only look “locally” miss the pattern entirely.

Refunds and voids are another quiet leak. Well-intentioned clarity around refunds, immediate status updates, explicit confirmations, predictable timelines can inadvertently confirm state. When a system responds differently to a valid versus invalid credential, attackers notice. Over time, those differences become part of the testing logic.

There’s also a structural assumption that acquirers will absorb the risk. Some merchants believe that if enumeration is widespread, the acquirer or network will filter it out upstream. Under VAMP, that assumption is backwards. Acquirers are now expected to show that they are pushing controls downward, not absorbing noise on behalf of merchants.

Finally, many teams underestimate how quickly patterns become visible outside their own dashboards. Fraud teams often ask, “Is this enough to worry about?” The uncomfortable answer is that by the time it feels serious locally, it may already be obvious at network level.

None of these blind spots indicate negligence. They indicate systems optimised for conversion and support, not for hostility toward learning attacks. In 2026, that distinction matters. Enumeration doesn’t exploit one big weakness. It exploits lots of small, reasonable decisions that add up to a usable testing surface.

Conclusion

For a long time, merchants could treat enumeration as an internal problem. Annoying, disruptive, but ultimately containable if no money moved and no chargebacks followed. Visa’s posture under VAMP removes that comfort. Enumeration is no longer judged only by outcome; it’s judged by what your traffic reveals about how your environment is being used.

That shift matters because it changes accountability. Merchants are no longer assessed purely on losses or disputes, but on whether their systems act as a learning surface for attackers. BIN-range testing doesn’t have to succeed to be damaging. It only has to be visible and in 2026, visibility exists far beyond any single dashboard.

For high-risk merchants in particular, this creates a narrower margin for error. Enumeration noise compounds existing scrutiny, accelerates acquirer intervention, and turns what used to be a fraud ops issue into a programme-level conversation. Not because anyone is being punitive, but because the network is actively trying to suppress behaviour that threatens its integrity.

The practical takeaway is simple, even if the execution isn’t. Enumeration prevention can no longer be reactive or cosmetic. It has to be designed into how payments behave, how failures respond, and how patterns look upstream. In the VAMP era, the question isn’t whether you blocked the attack. It’s whether your checkout made testing worthwhile at all.

FAQs

1. What is BIN-range card testing in simple terms?

It’s a form of enumeration where attackers test many card number combinations across a specific BIN or IIN range to identify which cards are valid. Most attempts fail, but the pattern itself creates risk.

2. Does enumeration count as fraud if no money is stolen?

Under Visa’s current posture, yes in a different sense. Enumeration is treated as behavioural misuse of the network, even if no successful fraud or chargebacks occur.

3. How is VAMP different from older monitoring programmes?

VAMP consolidates fraud, disputes, and enumeration into a single programme view. It focuses less on losses alone and more on patterns that indicate ecosystem risk.

4. Can a merchant trigger VAMP exposure without realising it?

Yes. Enumeration can be visible at network level long before it looks serious in a merchant’s own logs, especially when activity is distributed or low-and-slow.

5. Why is BIN-range testing riskier than testing individual cards?

Because it creates recognisable patterns tied to specific BINs, which are easier for schemes to correlate across merchants and acquirers.

6. Is rate limiting enough to stop enumeration in 2026?

On its own, no. Rate limiting helps locally, but Visa detects enumeration across the network. Controls must reduce learning behaviour, not just volume.

7. Why do high-risk merchants face faster escalation?

They already operate closer to issuer and acquirer thresholds. Enumeration noise compounds scrutiny, shortening tolerance and response times.

8. What typically triggers acquirer intervention?

Not a single event, but persistence: repeated enumeration patterns, abnormal decline behaviour, and evidence that an environment remains attractive for testing.

9. Does blocking all attempts immediately solve the problem?

It can stop losses, but it doesn’t always remove visibility. Consistent, predictable declines can still reinforce detectable patterns upstream.

10. Is enumeration mainly a bot problem?

Bots play a role, but the bigger issue is checkout behaviour. Retry logic, error messaging, and flow consistency often matter more than both sophistication.

11. What’s the biggest misconception merchants have about enumeration today?

That it’s only a fraud-ops concern. In 2026, enumeration is a continuity and programme-risk issue, not just a security one.

12. How should merchants think about enumeration going forward?

Not as something to clean up after it appears, but as a design constraint. The goal is to make testing unrewarding before it becomes visible at scale.