For years, fraud and risk systems have been built around a simple assumption: a transaction is either safe or unsafe. Rules fire, thresholds are crossed, and a binary decision follows approve or decline. This model worked when payment volumes were lower, settlement timelines were slower, and fraud patterns were easier to isolate. In 2026, it is increasingly out of step with reality.

High-volume payment environments expose the limitations of binary thinking very quickly. Millions of transactions sit in a grey area where outcomes are uncertain, intent is ambiguous, and impact varies widely. Treating all risk signals as equal or forcing them into a single yes-or-no outcome produces predictable problems: excessive false positives, inconsistent approvals, and poor capital efficiency. A low-value transaction with a moderate fraud probability is not equivalent to a high-value payout with a small chance of catastrophic loss, yet traditional systems often treat them the same.

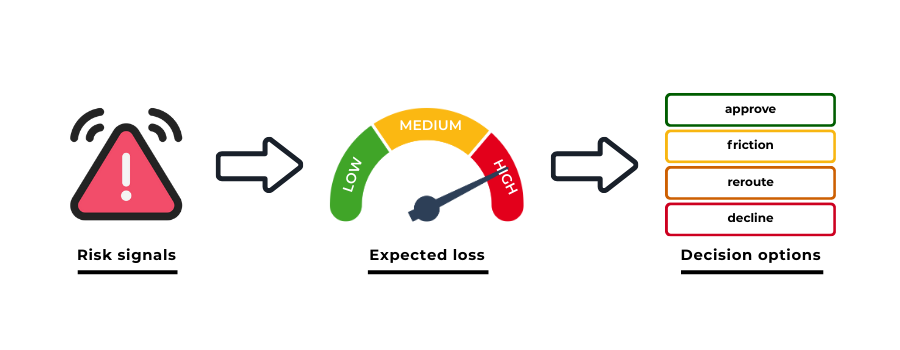

Modern risk frameworks are moving away from this rigidity. Instead of asking “Is this transaction fraudulent?”, they ask a more useful question: “What is the expected loss if this goes wrong?” That shift reframes risk as a probabilistic calculation, where likelihood and impact are evaluated separately and then combined. Fraud, disputes, regulatory exposure and operational loss can be measured in financial terms, rather than reduced to abstract scores.This change is not driven by academic theory alone. Faster payment rails, instant settlement and tighter capital constraints are forcing merchants, PSPs and acquirers to think about risk in the same way banks think about credit and liquidity as something to be priced, allocated and managed dynamically. Global policy discussions on financial risk measurement increasingly reinforce this view, recognising that uncertainty cannot be eliminated, only quantified and controlled. That perspective underpins much of the work published by organisations such as the Bank for International Settlements, which has long framed risk in terms of probability and impact rather than binary outcomes.

- Rules-Based vs Probabilistic Scoring: What Changed After 2024

- Likelihood × Impact: Scoring Fraud, Disputes, and Operational Loss Separately

- Use Cases: Low-Probability / High-Impact vs High-Probability / Low-Impact Events

- How Acquirers Interpret Probabilistic Risk Signals (Rewritten for flow)

- Threshold Design: Dynamic Cut-Offs by MCC, Region, and Payment Rail

- Explainability: How to Justify Probabilistic Declines to Regulators and Partners

- KPIs: Expected Loss per Transaction, Approval Elasticity, and Score Stability

- Conclusion

- FAQs

Rules-Based vs Probabilistic Scoring: What Changed After 2024

Rules-based scoring dominated fraud and risk management for decades because it offered clarity and control. Rules were easy to explain, easy to audit and relatively simple to implement. If a transaction exceeded a threshold or matched a known pattern, the system intervened. For a long time, this approach was “good enough.”

After 2024, however, several structural changes exposed the limits of rule-driven decisioning.

Why rules stopped scaling

The problem was not that rules became inaccurate, but that the environments they operated in changed faster than rules could adapt. Payment volumes increased, settlement times compressed and customer behaviour became more fluid across devices and channels.

Rules began to fail in predictable ways:

- They treated uncertainty as a failure condition

- They forced complex situations into binary outcomes

- They required constant manual tuning to stay relevant

As more edge cases emerged, rule sets grew larger and more brittle, often contradicting each other in high-volume scenarios.

What probabilistic models do differently

Probabilistic scoring reframes risk as a spectrum rather than a verdict. Instead of asking whether a rule is triggered, the system estimates the likelihood of an adverse outcome and evaluates what that outcome would cost if it occurred.

The post-2024 inflection point

Several developments accelerated the shift toward probabilistic thinking:

- Widespread adoption of instant and near-instant payment rails

- Higher regulatory scrutiny on operational and consumer harm

- Increased use of advanced analytics and behavioural data

- Pressure to optimise approval rates without increasing losses

These changes made it clear that risk could no longer be “blocked away.” It had to be measured, priced and absorbed intelligently.

Global standard-setting bodies have long advocated this approach in financial risk management. High-level guidance from organisations such as the Bank for International Settlements consistently frames risk in terms of expected loss rather than deterministic outcomes, a principle now being applied more broadly to payment and fraud decisioning.

Likelihood × Impact: Scoring Fraud, Disputes, and Operational Loss Separately

One of the most important shifts in probabilistic risk scoring is the recognition that not all losses are the same. In binary systems, fraud, disputes and operational failures are often collapsed into a single risk outcome. In 2026, advanced frameworks explicitly separate these dimensions and model them independently.

Why separating loss types matters

Fraud risk is only one source of financial exposure. Disputes, refunds, regulatory penalties and operational failures can each generate loss often with very different probability profiles and consequences.

For example:

- A transaction may have low fraud likelihood but high dispute probability

- Another may have high fraud likelihood but low financial impact

- A third may carry minimal fraud risk but material operational or settlement exposure

Treating these scenarios as equivalent distorts decision-making.

Likelihood and impact are different questions

Probabilistic frameworks decompose risk into two components:

- Likelihood, how probable is an adverse outcome?

- Impact: how costly would that outcome be if it occurs?

This allows systems to evaluate expected loss rather than raw risk signals.

To illustrate how this works in practice:

| Risk Dimension | Likelihood Focus | Impact Focus |

| Fraud | Probability of unauthorised activity | Transaction value, recovery cost |

| Disputes | Probability of chargeback or refund | Fees, penalties, operational overhead |

| Operational loss | Probability of processing failure | Settlement delay, liquidity impact |

This separation enables more nuanced decisions. A low-likelihood, high-impact payout may warrant intervention even if fraud signals are weak. Conversely, a high-likelihood, low-impact dispute risk may be acceptable within tolerance thresholds.

Expected loss becomes the decision anchor

Once likelihood and impact are modelled independently, they can be combined into an expected loss figure. This does not dictate a single outcome, but it provides a rational basis for choosing between options:

- Approve and absorb risk

- Apply friction to reduce likelihood

- Delay or reroute to reduce impact

- Decline when expected loss exceeds tolerance

This mirrors how financial institutions have long approached credit and market risk.

International standards bodies have consistently framed risk management in these terms. High-level principles published by organisations such as the Bank for International Settlements emphasise that uncertainty should be quantified and managed through expected loss, not eliminated through blunt controls.

Key takeaway

When likelihood and impact are separated, risk scoring stops being a gatekeeping function and becomes a loss-management tool. That shift is what makes probabilistic models practical at scale.

Use Cases: Low-Probability / High-Impact vs High-Probability / Low-Impact Events

Probabilistic risk models become most valuable when they are applied to real-world trade-offs rather than abstract scores. In high-volume payment environments, the majority of transactions fall into one of two categories: events that are unlikely but catastrophic if they occur, and events that are frequent but relatively cheap to absorb. Binary decisioning struggles with both.

Low-probability, high-impact events

These scenarios occur infrequently, but when they do, the consequences are severe. Traditional rules often underreact because the likelihood appears small.

Typical examples include:

- Large outbound payouts with limited recovery options

- Cross-border transactions exposed to regulatory or sanctions risk

- Wallet withdrawals that could trigger cascading liquidity effects

In these cases, even a small probability warrants intervention because the downside is asymmetric. Probabilistic models surface this imbalance clearly by assigning a high expected loss despite low likelihood.

High-probability, low-impact events

At the other end of the spectrum are events that happen often but carry limited financial damage. Rules-based systems frequently overreact here, creating unnecessary friction.

Common examples include:

- Small-value disputes in card-heavy markets

- Refund abuse with capped exposure

- Benign customer errors that trigger retries

Blocking these events aggressively often costs more in lost revenue and support overhead than the risk itself.

Why probabilistic framing changes decisions

By evaluating likelihood and impact separately, systems can respond proportionately rather than uniformly. The same probability does not justify the same control when impact differs by orders of magnitude.

| Scenario Type | Likelihood Profile | Appropriate Response |

| Rare, catastrophic loss | Low | Delay, review, or additional controls |

| Frequent, minor loss | High | Allow within tolerance thresholds |

| Moderate likelihood and impact | Medium | Targeted friction or rerouting |

This approach enables risk teams to align controls with economic reality rather than abstract thresholds.

From fraud prevention to loss optimisation

What changes in practice is mindset. The question is no longer “Can this go wrong?” but “Is this an acceptable loss if it does?” This reframing allows organisations to deploy capital and controls where they matter most.

Public-sector economic analysis frequently applies this logic when evaluating uncertainty and systemic exposure. Broader policy work published by bodies such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reflects the same principle: risk should be managed through proportional response, not eliminated at all costs.

How Acquirers Interpret Probabilistic Risk Signals (Rewritten for flow)

For acquirers, probabilistic risk signals are not theoretical constructs; they are practical inputs into how exposure is priced, capped, and monitored across merchant portfolios. As scoring frameworks move from binary outcomes to likelihood × impact models, acquirers are recalibrating how they interpret risk information provided by merchants and PSPs.

Historically, acquirer decisioning relied on hard outcomes. Transactions were either acceptable or not, and risk conversations tended to focus on incident response. Probabilistic scoring changes this dynamic. Instead of reacting to individual events, acquirers increasingly evaluate expected exposure over time, how risk accumulates across transactions, corridors, and payment rails, and whether that exposure remains within defined tolerance.

This shift matters because acquirers do not manage risk transaction by transaction. They manage it at portfolio level. A single transaction with elevated likelihood may be acceptable if the potential loss is limited and recoverable. By contrast, repeated moderate-risk activity can become a concern even when no single event appears severe. Probabilistic signals allow acquirers to see these patterns early, without forcing premature intervention.

What acquirers value most in probabilistic inputs is stability. Volatile scores that swing dramatically from one transaction to the next are less useful than consistent distributions that reflect underlying behaviour.

When likelihood and impact are measured separately, acquirers can distinguish between temporary spikes and structural risk trends, which informs decisions around pricing, reserves, routing, or enhanced monitoring.

There are three questions acquirers typically try to answer when reviewing probabilistic risk data:

- Is the expected loss bounded and understood?

- Does risk concentrate in specific contexts (MCC, region, rail), or is it diffuse?

- Are controls in place to prevent tail-risk events from cascading?

Importantly, a higher probability signal does not automatically trigger concern. Acquirers interpret probability in relation to impact and reversibility. A high probability of a small, recoverable loss is fundamentally different from a low probability of an irreversible one. Probabilistic frameworks make this distinction explicit rather than implicit.

This interpretation aligns closely with established risk-based regulatory thinking. International standards around financial crime and risk management consistently emphasise proportionality, materiality, and ongoing assessment over zero-tolerance thresholds. Guidance published by bodies such as the Financial Action Task Force reflects this approach, framing risk as something to be assessed and mitigated rather than categorically avoided.

Threshold Design: Dynamic Cut-Offs by MCC, Region, and Payment Rail

In probabilistic risk frameworks, thresholds are no longer static pass–fail markers. They are contextual decision boundaries that flex depending on what kind of risk is being evaluated and where that risk sits economically. By 2026, the idea of a single global cut-off has largely disappeared from advanced payment environments.

Fixed thresholds assumed that a score carried the same meaning everywhere. In practice, a risk signal only becomes meaningful when it is interpreted against context. A moderate fraud likelihood may be trivial in one scenario and unacceptable in another. Static cut-offs fail because they flatten those distinctions.

Merchant category changes the economics of risk

The merchant category is often the first dimension where probabilistic thresholds diverge. Different categories carry different blends of fraud exposure, dispute behaviour, regulatory scrutiny, and recoverability. A category with frequent low-value disputes behaves very differently from one where losses are rare but severe.

Probabilistic frameworks allow thresholds to be set against expected loss rather than raw probability. This means a higher likelihood may still be tolerated if impact is limited, while even small likelihoods trigger intervention when downside risk is asymmetric. The threshold is no longer about fear; it is about economic materiality.

Geography introduces recovery reality

Regional context further reshapes threshold design. Markets differ in consumer behaviour, banking infrastructure, dispute resolution timelines, and legal recovery options. A transaction that is marginally risky in one jurisdiction may be materially risky in another simply because recovery paths differ.

Dynamic thresholds encode this reality. They allow the same probabilistic signal to trigger different responses depending on whether loss can be reversed, delayed, or absorbed. This prevents over-enforcement in resilient markets and under-protection in fragile ones.

Payment rails redefine urgency

Payment rails ultimately determine how much time and control exist once a transaction is approved. Card payments, open banking transfers, wallets, and instant rails all impose different constraints on reversibility and settlement.

As settlement speed increases, tolerance for uncertainty shrinks. In instant-payment environments, thresholds often tighten not because fraud likelihood rises, but because impact becomes immediate and irreversible. Probabilistic models reflect this by adjusting cut-offs to the consequences of being wrong, not just the chance.

From enforcement to steering

What changes most is the purpose of thresholds themselves. They stop being blunt enforcement tools and become steering mechanisms. Instead of deciding only whether to block or allow, thresholds guide when to apply friction, when to reroute transactions, and when absorbing loss is an acceptable cost of growth.

This approach aligns with broader UK regulatory expectations around proportionality and risk-based controls, where decisioning is expected to reflect context and materiality rather than rigid uniformity.

Key takeaway

Dynamic thresholds recognise that risk has meaning only in context. By adjusting cut-offs across category, geography, and rail, probabilistic frameworks replace rigid enforcement with economically rational judgement.

Explainability: How to Justify Probabilistic Declines to Regulators and Partners

Why “the model said so” no longer works

As risk scoring frameworks shift toward probabilistic decisioning, explainability becomes as important as accuracy. In binary systems, justification was simple: a rule was triggered, a threshold was crossed, and the transaction was declined. Probabilistic models remove that simplicity. Decisions are no longer driven by a single condition, but by an assessment of expected loss under uncertainty.

By 2026, regulators, acquirers, and scheme partners increasingly expect firms to explain why a probabilistic decline made sense in economic terms, not just how the model arrived there. “High risk” is no longer a sufficient explanation. The decision must be grounded in likelihood, impact, and proportional response.

Framing declines around expected loss

Effective explainability reframes declines away from suspicion and toward economics. Instead of asserting that a transaction was fraudulent, firms explain that the expected loss exceeded tolerance given the context. This distinction matters, particularly when dealing with trusted customers or regulated partners.

A probabilistic explanation typically addresses three elements:

- What outcome was being guarded against

- How likely that outcome was in this context

- Why the potential impact justified intervention

This approach allows decisions to be defended without implying wrongdoing, which is especially important in customer-facing and regulatory conversations.

Making probabilistic logic intelligible

One of the misconceptions about probabilistic models is that they are inherently opaque. In practice, well-designed frameworks can be more explainable than rule stacks, because they expose underlying assumptions explicitly. Likelihood and impact are intuitive concepts. When surfaced clearly, they provide a narrative that non-technical stakeholders can understand.

For partners such as acquirers, explainability often takes the form of distributions and trends rather than point decisions. Showing how expected loss evolves over time, or how it concentrates in specific contexts, builds confidence that controls are systematic rather than arbitrary.

Regulatory expectations and proportionality

From a regulatory perspective, explainability is closely tied to proportionality and fairness. Automated decisions that materially affect users must be justifiable, reviewable, and aligned with stated risk policies. UK regulatory guidance consistently emphasises that firms should be able to demonstrate how automated decisioning reflects risk-based judgement rather than blanket exclusion.

High-level UK government guidance on automated and risk-based decision-making reinforces the principle that controls should be transparent, proportionate, and defensible particularly when probabilistic assessments influence access to services.

KPIs: Expected Loss per Transaction, Approval Elasticity, and Score Stability

Why traditional fraud KPIs fall short

As risk scoring shifts toward probabilistic models, many legacy performance metrics lose relevance. Metrics such as raw fraud rate or decline percentage offer limited insight when decisions are no longer binary. They tell you what was blocked, but not whether the outcome was economically rational.

In probabilistic frameworks, success is measured by how well uncertainty is managed, not how aggressively it is eliminated. This requires KPIs that reflect expected outcomes rather than isolated events.

Expected loss per transaction as the anchor metric

Expected loss per transaction has emerged as one of the most meaningful indicators in likelihood × impact models. It captures both dimensions of risk in a single economic measure, allowing teams to compare very different scenarios on equal footing.

Rather than asking whether fraud occurred, this KPI asks whether the system’s decisions kept loss within tolerance over time. A portfolio with occasional losses but low expected loss may be healthier than one with zero incidents but excessive friction and suppressed approvals.

This metric also enables clearer conversations with finance, treasury, and acquirers, because it translates risk performance into financial language rather than abstract scores.

Approval elasticity reveals decision quality

Approval elasticity measures how approval rates respond to changes in risk tolerance. In well-calibrated probabilistic systems, small increases in tolerance should produce predictable, proportional gains in approvals without sudden spikes in loss.

When elasticity behaves erratically, it is often a sign that likelihood and impact are not being separated cleanly, or that thresholds are misaligned with context. Stable elasticity suggests that the model understands where value lies and where it does not.

Score stability reflects model maturity

Score stability is frequently overlooked, yet it is critical in probabilistic environments. Mature models produce distributions that evolve gradually as behaviour changes. Immature or overfitted models swing sharply from one period to the next, making them difficult to govern or explain.

Stable scores do not mean static risk. They mean that shifts reflect genuine changes in underlying behaviour rather than noise. This stability is what allows probabilistic frameworks to support long-term planning rather than reactive firefighting.

KPIs as governance tools, not just performance metrics

In 2026, these KPIs increasingly serve a governance function. They demonstrate that risk is being measured, tolerated, and controlled deliberately. Public-sector economic and risk-management thinking consistently frames uncertainty in terms of expected outcomes rather than absolute prevention, a principle reflected broadly across UK policy discussions on proportional and accountable decision-making.

Conclusion

By 2026, the most meaningful change in risk scoring is not technological but conceptual. The industry is moving away from the idea that risk can be cleanly blocked at the point of transaction, and toward the understanding that risk must be measured, priced, and managed over time. Likelihood × impact models reflect this shift by treating uncertainty as something to be quantified rather than feared.

Binary decisioning made sense when payment systems were slower, volumes were lower, and loss events were easier to isolate. In modern, high-volume environments, that logic breaks down. A rigid approve-or-decline mindset obscures the economic reality that not all risks are equal, not all losses are material, and not all uncertainty warrants intervention. Probabilistic frameworks restore that nuance by anchoring decisions in expected loss rather than abstract scores.

In that sense, modern risk scoring is no longer just about stopping bad transactions. It is about allocating risk capacity intelligently deciding where capital, friction, and attention are best spent in an environment where uncertainty is unavoidable.

FAQs

1. Why are binary fraud decisions no longer effective in 2026?

Binary decisions force complex, uncertain situations into simplistic outcomes. In high-volume, fast-settlement environments, this leads to excessive false positives and poor capital efficiency. Probabilistic models reflect reality more accurately by evaluating uncertainty rather than denying it.

2. What does “likelihood × impact” mean in risk scoring?

It means assessing both the probability of something going wrong and the financial or operational consequence if it does. Risk decisions are then based on expected loss rather than raw suspicion or static thresholds.

3. How is probabilistic scoring different from traditional fraud scoring?

Traditional scoring focuses on detecting fraud signals. Probabilistic scoring evaluates multiple types of loss fraud, disputes, and operational risk and quantifies them economically, enabling proportionate responses instead of blanket blocks.

4. Does probabilistic scoring mean accepting more fraud?

No. It means tolerating manageable loss while preventing material loss. Controls are applied where impact is highest, rather than evenly across all uncertainty.

5. Why do acquirers prefer probabilistic risk signals?

Because they align with how acquirers manage exposure at portfolio level. Expected loss, volatility, and concentration are more actionable than binary approve/decline outcomes.

6. How do probabilistic models improve customer experience?

They reduce unnecessary declines and friction by allowing low-impact risk to pass while intervening decisively in high-impact scenarios. This improves approval rates without weakening controls.

7. Are probabilistic declines harder to explain to regulators?

Not when designed correctly. Framing decisions around expected loss, proportionality, and risk tolerance often produces clearer justifications than opaque rule stacks.

8. What KPIs matter most in probabilistic risk frameworks?

Expected loss per transaction, approval elasticity, and score stability are the most meaningful indicators of whether a probabilistic model is working as intended.