For years, chargeback prevention and chargeback recovery were treated as separate disciplines. Prevention focused on reducing disputes through fraud controls and customer communication. Recovery began only after a dispute was filed, when teams scrambled to gather documents, screenshots, and logs in the hope of winning representment. In 2026, that separation no longer makes sense.

The reality is that most disputes are decided long before evidence is ever submitted. By the time a chargeback is filed, the outcome is often predetermined by whether evidence already exists, whether it is coherent, and whether it aligns with scheme expectations. Merchants that rely on post-dispute evidence collection are not just slower; they are structurally disadvantaged.

This is where the idea of “compelling evidence by design” becomes critical. Rather than asking, “What evidence can we assemble now?”, leading merchants ask, “What evidence should already exist if this transaction is disputed later?” The shift is subtle but transformative. Evidence stops being a reactive artefact and becomes a product of system design, data integration, and operational intent.

The 2025 edition of the Mastercard Chargeback Guide reinforces this shift. While it is framed as a procedural reference, its underlying message is practical: successful representment depends on relevance, clarity, and timeliness not volume. Evidence that is fragmented, delayed, or inconsistently captured rarely meets scheme standards, regardless of how much of it is submitted.

For merchants operating in high-risk or high-volume environments, this has strategic implications. Winning more disputes does not come from fighting harder; it comes from building systems that make disputes easier to prevent and simpler to defend when prevention fails. Evidence becomes infrastructure embedded across checkout, fulfilment, customer support, and refunds rather than a last-minute compilation exercise.

In the sections that follow, we’ll translate the 2025 guidance into practical design principles, showing how merchants can layer evidence, reduce “unrecognised transaction” disputes, prove digital consumption responsibly, and decide when representment is worth pursuing at all.

- What the 2025 Chargeback Guide Implies for Merchants

- Evidence Layers: Order Proof, Delivery Proof, Usage Proof, Cancellation / Refund Proof

- Descriptor and Receipt Strategy: Reducing “I Don’t Recognise This” Disputes

- Digital Goods and Services: How to Prove Consumption Without Violating Privacy

- Refund Automation: When to Refund vs Represent (Decision Matrix)

- Building an Evidence Pipeline: CRM + PSP + Shipping + Product Telemetry

- Why evidence fails without a pipeline

- CRM: capturing customer intent and resolution history

- PSP and payments layer: transaction truth

- Fulfilment or delivery systems: proving availability

- Product or service telemetry: demonstrating access without intrusion

- How the pipeline supports automation and outcomes

- KPIs: Representment Win Rate, Time-to-Evidence, Dispute Root Cause Drift

- Conclusion

- FAQs

What the 2025 Chargeback Guide Implies for Merchants

Merchants often approach scheme chargeback guides as operational manuals: documents to consult only after a dispute has already been filed. Read that way, the 2025 Chargeback Guide can feel dense, procedural, and reactive. Read properly, however, it signals a more fundamental shift in how disputes are expected to be handled and, critically, how evidence should be prepared long before a dispute exists.

Evidence relevance now outweighs evidence volume

One of the clearest signals in the 2025 guidance is that more documentation does not mean better representation. The guide repeatedly emphasises relevance, clarity, and alignment with the dispute context. For merchants, this implies that indiscriminate evidence collection is no longer just inefficient; it can actively weaken a case. Submitting screenshots, logs, or records that do not directly address the cardholder’s claim creates noise, slows review, and undermines credibility.

The practical implication is that evidence must be designed to answer specific dispute narratives. Order confirmation alone is not enough. Nor is proof of delivery in isolation. Each piece of evidence should exist because it resolves a likely challenge, not because it is available.

Timeliness is a systems problem, not a team problem

Another strong implication of the guide is that representation timelines are unforgiving by design. Response windows assume that merchants can retrieve, validate, and submit evidence quickly. This is not a staffing expectation; it is a systems expectation.

Teams that rely on manual data gathering or cross-department requests are structurally misaligned with how disputes are now processed.

From a practical standpoint, this shifts accountability upstream. If evidence cannot be accessed within hours or days, the issue is not analyst performance it is architectural. The guide implicitly rewards merchants that have built evidence availability into their transaction, fulfilment, and support flows.

Consistency is evaluated even when not explicitly stated

While the guide does not explicitly score merchants on consistency, its structure assumes it. Evidence expectations are framed in a way that presumes similar disputes will be handled similarly. For merchants, this means that ad-hoc or case-by-case improvisation introduces risk. Two disputes with the same underlying issue should not produce entirely different evidence packs.

Consistency matters because it shapes issuer confidence. When evidence patterns vary wildly, even strong individual cases can begin to look unreliable. The guide’s emphasis on standardised evidence categories signals that predictable, repeatable documentation is now part of representation quality.

Representment viability is increasingly predictable

Perhaps the most overlooked implication is that the guide makes representation outcomes more predictable than many merchants assume. By clearly outlining what constitutes compelling evidence for different dispute scenarios, it also highlights when such evidence is unlikely to exist. In those cases, fighting a dispute becomes an exercise in cost accumulation rather than recovery.

Merchants that read the guidance strategically use it to decide when not to represent. This is not capitulation; it is optimisation. The guide effectively draws a line between disputes that can be defended with designed evidence and those that should be resolved earlier through refunds or customer resolution.

These implications are not theoretical. They are embedded throughout the 2025 guidance, which positions evidence quality, relevance, and readiness as the foundation of effective dispute management rather than a last-stage tactic.

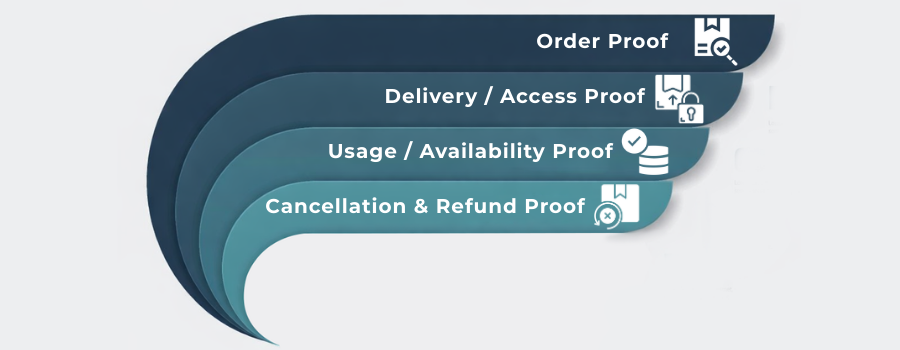

Evidence Layers: Order Proof, Delivery Proof, Usage Proof, Cancellation / Refund Proof

Compelling evidence is rarely a single document. In practice, disputes are won or lost based on whether multiple layers of evidence reinforce the same narrative. When one layer is missing or weak, the entire case becomes vulnerable even if other elements appear strong. Designing evidence “by layer” allows merchants to build cases that are coherent, proportionate, and resilient.

Layer 1: Order proof

Order proof establishes that a transaction was intentionally initiated by the customer. It anchors legitimacy and provides the baseline against which all other evidence is evaluated. Without it, downstream proof struggles to carry weight.

Strong order proof typically demonstrates:

- Clear linkage between the customer and the transaction

- Confirmation that key details (amount, date, merchant identity) were presented

- Evidence that the order was successfully completed, not merely attempted

Weak order proof often fails because it exists in isolation – for example, a receipt without any supporting context around how the order was placed or acknowledged.

Layer 2: Delivery proof

Delivery proof answers a different question: was the promised value actually made available? For physical goods, this often involves logistics data. For services or access-based products, delivery is less tangible but no less important.

This layer works best when it shows:

- That delivery or access occurred after the order

- That it was consistent with what was purchased

- That it aligns temporally with the transaction

Delivery proof that cannot be clearly tied back to the original order weakens the overall narrative, even if delivery itself occurred.

Layer 3: Usage or consumption proof

Usage proof is the most sensitive layer, particularly for digital goods and services. Its purpose is not to surveil customers, but to demonstrate that value was consumed or accessed in a way consistent with legitimate use.

Effective usage proof is:

- Behavioural rather than intrusive

- Time-bound and proportional

- Clearly linked to the purchased service or content

Logs that demonstrate access, session initiation, or feature use often carry more weight than raw technical data. Importantly, this layer must be designed with privacy in mind. Evidence should show that usage occurred, not expose how a customer behaved in detail.

Guidance from the UK Information Commissioner’s Office reinforces this proportionality principle, emphasising that organisations should collect and retain only the data necessary for a defined purpose including dispute resolution and no more.

Layer 4: Cancellation and refund proof

This layer often determines outcomes in disputes driven by confusion rather than fraud. It establishes whether the customer had a clear opportunity to cancel, whether refund policies were transparent, and whether any refund was processed appropriately.

Effective cancellation and refund proof shows:

- That policies were available and understandable

- Whether the customer attempted cancellation

- How and when refunds were issued, if applicable

When this layer is missing, even strong order and usage proof may not be enough to counter customer claims.

Why layering matters

Each layer reinforces the others. Order proof without delivery looks incomplete. Delivery without usage can appear ambiguous. Usage without clear cancellation terms may still invite disputes. Merchants that design evidence pipelines with all four layers in mind produce cases that feel intentional rather than assembled under pressure.

Descriptor and Receipt Strategy: Reducing “I Don’t Recognise This” Disputes

A large share of disputes categorised as “unrecognised transactions” are not driven by fraud. They are driven by memory failure. Customers look at a bank statement days or weeks later and cannot connect a transaction line item to a genuine purchase they once made. When that connection fails, a dispute becomes the default path.

This is why descriptor and receipt design matter far more than many merchants assume. These elements are not administrative details; they are recognition tools. When they fail, disputes follow regardless of how strong the underlying transaction was.

Why descriptors fail customers

Most descriptor problems stem from a disconnect between how a merchant thinks about its business and how a customer remembers it. Legal entity names, truncated descriptors, or backend platform identifiers may be technically accurate, but they rarely match what a customer recalls at statement time.

In modern banking interfaces, where transaction lists are compressed and abbreviated, these weaknesses are amplified. A descriptor that is “technically correct” but cognitively unclear still invites disputes.

Receipts as recognition anchors, not just confirmations

Receipts are often treated as proof of purchase. In practice, they are memory anchors. A well-designed receipt helps a customer reconstruct why they paid, not just that they paid.

Effective receipts reinforce:

- The brand name exactly as it appears on statements

- What was purchased, in plain language

- When the transaction occurred and what to expect next

Receipts that focus only on order numbers or internal references do little to prevent disputes later. If a customer searches their inbox during a moment of doubt, the receipt should immediately resolve uncertainty rather than create more questions.

Designing descriptors and receipts together

The biggest mistake merchants make is treating descriptors and receipts as separate systems. When the descriptor says one thing and the receipt says another, customers are forced to reconcile two identities and many simply give up and dispute.

From a consumer-protection perspective, clarity of merchant identity and communication is a recognised expectation. UK guidance on transparent consumer transactions emphasises that customers should be able to easily identify who they paid and why, particularly when resolving billing queries. This principle underpins dispute prevention just as much as formal evidence does. You can see this reflected in official UK consumer transparency guidance on payments and refunds, which stresses clear identification and communication as part of fair treatment.

Why this matters for evidence by design

Recognition disputes are among the easiest to prevent and the hardest to defend after escalation. No amount of backend logging can replace a customer simply recognising a charge. Merchants that engineer clarity into descriptors and receipts reduce disputes before evidence is ever needed and avoid spending time fighting cases that should never have existed.

Digital Goods and Services: How to Prove Consumption Without Violating Privacy

Disputes involving digital goods and services expose a fundamental tension in chargeback evidence: the value delivered is real, but it is intangible. Unlike physical delivery, consumption cannot be photographed, signed for, or tracked through logistics partners. As a result, many merchants either under-prove usage or over-collect data in ways that weaken their position rather than strengthen it.

The key shift in 2026 is recognising that disputes over digital goods are rarely about whether access was technically possible.

They are about whether a merchant can credibly demonstrate that access was made available and reasonably usable in line with what was sold.

Why consumption is harder to prove than delivery

Digital fulfilment happens instantly and often invisibly. Access is granted, features are unlocked, content becomes available and all of this may occur within seconds of payment. By the time a dispute is raised, weeks or months later, the customer’s memory of that access may be vague, especially if usage was brief or intermittent.

This makes traditional “proof” insufficient. A simple timestamp showing account creation or feature activation does not always align with how customers perceive value. Evidence must therefore bridge the gap between system events and customer understanding.

What constitutes proportional usage evidence

Effective usage evidence does not attempt to reconstruct every action a customer took. Instead, it focuses on demonstrating that meaningful access occurred in a way consistent with the product sold.

Proportional usage evidence typically shows:

- That access credentials were issued successfully

- That the customer authenticated into the service after purchase

- That the core service or content was technically available during the relevant period

This approach avoids deep behavioural tracking while still answering the core dispute question: was the service made available as promised?

Overly granular logs page-by-page activity, detailed session recordings, or behavioural heatmaps often add little evidentiary value and can raise questions about data handling rather than strengthen a case.

Privacy as an evidence design constraint

Privacy is not a limitation on evidence quality; it is a design requirement. Evidence that appears invasive, excessive, or unrelated to the dispute narrative can undermine credibility with issuers and reviewers. In contrast, evidence that is clearly scoped, relevant, and minimal tends to be easier to interpret and more persuasive.

This aligns with established UK data protection principles, particularly the expectation that organisations collect and retain only the data necessary for a specific purpose. When usage evidence is designed around necessity and relevance, it supports both dispute defence and lawful data handling. This principle is reflected in the UK Information Commissioner’s Office guidance on data minimisation, which emphasises proportional data use for defined purposes such as contractual performance and dispute resolution.

Designing usage proof that survives scrutiny

Merchants that consistently win digital-goods disputes design usage evidence upstream. Access events, authentication records, and service availability indicators are captured automatically and stored in a way that makes them easy to retrieve later. Crucially, these signals are framed to explain what was available and when, not to monitor customer behaviour in detail.

When disputes arise, this evidence feels intentional rather than assembled. It tells a clear story without overwhelming reviewers, and it aligns with both scheme expectations and privacy norms. In practice, this balanced clarity without intrusion is what makes digital consumption proof credible in 2026.

Refund Automation: When to Refund vs Represent (Decision Matrix)

Refund automation is often misunderstood as a concession strategy. In reality, it is a loss-avoidance mechanism. By 2026, the cost of fighting unwinnable disputes in fees, ratios, operational effort, and downstream monitoring pressure often exceeds the value of the transaction itself. Automation allows merchants to make this trade-off deliberately, rather than under deadline pressure.

The goal is not to refund more, but to refund earlier when outcomes are predictable, and to reserve representation for cases where evidence strength and economic return justify the effort.

Why automation is required for consistency

Manual refund or representment decisions rarely scale cleanly. Analysts under time pressure tend to default either to caution (refund everything) or optimism (fight everything). Both behaviours create drift over time. Automation introduces discipline by enforcing the same logic across similar scenarios, regardless of volume or staffing conditions.

More importantly, automation ensures that decisions are anchored in evidence availability, not subjective judgement. If the evidence layers required for a credible case do not exist at the point of alert or dispute, the system should not assume they will materialise later.

Decision matrix: refund vs represent

The matrix below illustrates how automation frameworks typically distinguish between cases that should be refunded and those worth representing. It is intentionally simplified the purpose is to show decision logic, not exhaust every scenario.

| Evidence and context signal | Automated action | Rationale |

| Weak or missing usage evidence | Refund | Low probability of representment success |

| Clear cancellation attempt before fulfilment | Refund | High likelihood of customer-side legitimacy |

| Strong layered evidence across order, delivery, and usage | Represent | Defensible narrative aligned with scheme expectations |

| Transaction value below recovery threshold | Refund | Costs outweigh potential recovery |

Automation applies these rules consistently, preventing emotional or ad-hoc decisions when dispute volumes spike.

How automation uses evidence layers

Refund automation does not operate in isolation. It consumes signals produced by the evidence layers discussed earlier in this guide. When order proof is present but usage proof is absent, the system recognises a structural weakness. When cancellation logs show customer intent prior to fulfilment, automation deprioritises representation.

This linkage ensures that decisions are explainable. If a case is refunded, the reason is traceable to missing or weak evidence. If it is represented, the system can demonstrate that the necessary layers were already in place.

Guardrails to prevent over-refunding

Automation without guardrails can create new risks. Well-designed systems therefore include limits that prevent refund logic from being exploited or drifting too far.

Common safeguards include:

- Caps on refund frequency per customer or account

- Pattern detection for repeated “refund-first” behaviour

- Exception routing for high-value or anomalous cases

These controls ensure that automation supports prevention without turning refunds into an incentive.

From a governance perspective, automated refund decisions must still align with expectations around fair and proportionate customer treatment. UK guidance on refunds and consumer rights reinforces that refunds should be applied consistently and transparently, not arbitrarily. Embedding this principle into automation logic helps merchants demonstrate that early refunds are controlled decisions, not blanket concessions. This expectation is reflected in official UK government guidance on accepting returns and issuing refunds, which outlines when refunds are appropriate and how they should be handled fairly.

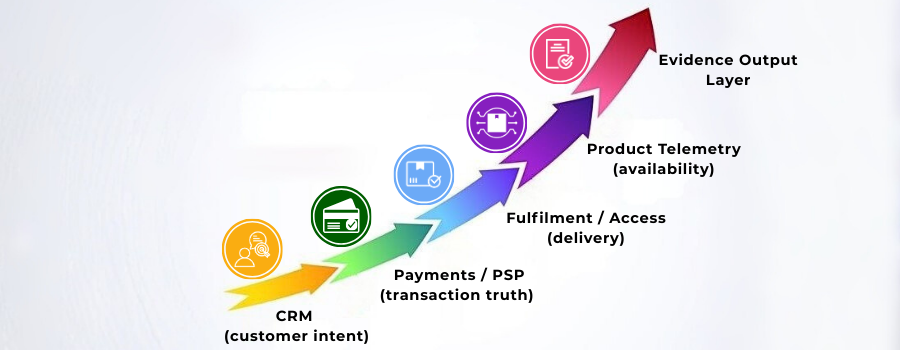

Building an Evidence Pipeline: CRM + PSP + Shipping + Product Telemetry

Compelling evidence does not emerge from a single system. It emerges when multiple systems produce aligned signals that can be assembled quickly into a coherent narrative. Merchants that struggle with representation rarely lack data; they lack a pipeline that connects it. In 2026, evidence quality is less about what you store and more about how reliably those systems talk to each other.

Why evidence fails without a pipeline

When evidence lives in silos, time becomes the enemy. Analysts wait on exports, reconcile mismatched identifiers, or chase confirmations across teams. By the time information is assembled, deadlines are tight and context is lost. This is not a training issue, it is an architectural one. A pipeline reduces latency and ambiguity by design, ensuring that evidence can be retrieved and interpreted without manual stitching.

CRM: capturing customer intent and resolution history

The CRM layer anchors why a customer contacted you and what they attempted to do before escalating. It provides the human context behind a dispute.

At minimum, this layer should reliably surface:

- Records of cancellation or refund requests

- Time-stamped customer communications and responses

When CRM signals are accessible alongside transaction data, disputes driven by confusion or unmet expectations are easier to identify and resolve early.

PSP and payments layer: transaction truth

The payments layer provides the canonical record of the transaction itself. It establishes what happened at the moment of payment and immediately after.

This layer typically contributes:

- Transaction identifiers and timestamps

On its own, this data is rarely decisive. Its value increases dramatically when it can be correlated with fulfilment and usage signals downstream.

Fulfilment or delivery systems: proving availability

Whether a product is shipped, provisioned, or unlocked, fulfilment systems answer the question of when value became available. For physical goods, this may involve dispatch and delivery confirmation. For digital services, it may be access provisioning or account activation.

The critical requirement is correlation: fulfilment events must be clearly linked back to the original order and payment. Without that linkage, delivery evidence loses persuasive power.

Product or service telemetry: demonstrating access without intrusion

Telemetry completes the picture by showing that the service was accessible and usable after fulfilment. Done well, it avoids invasive monitoring while still demonstrating that the merchant delivered what was promised.

Effective telemetry focuses on:

- Access or session initiation events

- Availability windows aligned to the purchase period

These signals are strongest when they confirm availability rather than scrutinise behaviour. Designed proportionately, they strengthen evidence while respecting privacy boundaries discussed earlier.

How the pipeline supports automation and outcomes

When these systems are connected, evidence becomes a flow rather than a scramble. Automation can assess evidence completeness in near-real time, route cases toward refund or representation consistently, and reduce time-to-evidence dramatically. Just as importantly, the same pipeline supports auditability and governance by making decisions explainable.

UK supervisory expectations consistently emphasise the importance of effective systems and controls to manage operational risk. Guidance on operational resilience and record integrity reinforces that firms should design systems that reliably support critical processes, including dispute handling and customer outcomes. This expectation is reflected in the Financial Conduct Authority’s principles on systems and controls, which underline the need for coherent, well-governed operational infrastructure.

KPIs: Representment Win Rate, Time-to-Evidence, Dispute Root Cause Drift

As dispute processes become more automated and evidence is designed upstream, traditional chargeback ratios alone no longer tell the full story. In 2026, mature merchants track a smaller set of KPIs that reveal how effectively evidence systems are working, not just how many disputes are won or lost. These metrics focus on quality, speed, and structural change.

Representment win rate: quality over volume

Representment win rate remains relevant, but only when interpreted correctly. A rising win rate does not necessarily mean disputes are decreasing; it often indicates that merchants are becoming more selective about which cases they fight.

When refund automation filters out weak cases early, the remaining representation pool is stronger by design.

What this KPI signals when used properly:

- Evidence quality is improving across defended cases

- Analysts are not spending time on predictable losses

What it does not signal on its own:

- Total dispute exposure

- Customer satisfaction or prevention success

A stable or modestly increasing win rate, combined with fewer total disputes, is often healthier than an inflated win rate driven by aggressive filtering alone.

Time-to-evidence: speed as a structural advantage

Time-to-evidence measures how quickly a merchant can assemble a complete, coherent evidence package once a dispute or alert is triggered. In practice, this KPI reflects system integration maturity more than team performance.

As evidence pipelines mature, this metric typically collapses from days to hours or minutes. Crucially, time-to-evidence exposes architectural weaknesses. Persistent delays almost always point to siloed systems or manual joins rather than staffing issues.

Dispute root cause drift: detecting upstream failure early

Root cause drift tracks how the mix of dispute reasons changes over time. It answers a different question: are disputes evolving because customer behaviour is changing, or because internal processes are degrading?

Monitoring drift allows teams to intervene before disputes spike, turning KPIs into early-warning signals rather than post-mortems.

How these KPIs work together

| KPI | What it really measures | Why it matters |

| Representment win rate | Evidence quality in defended cases | Confirms selective, disciplined defence |

| Time-to-evidence | System integration maturity | Determines speed and viability of outcomes |

| Root cause drift | Upstream operational health | Flags emerging dispute drivers early |

Taken together, these metrics show whether “evidence by design” is actually delivering operational leverage.

From a governance perspective, regulators increasingly expect firms to monitor not just outcomes, but the effectiveness of controls that produce them. UK guidance on monitoring systems and operational outcomes reinforces the importance of using meaningful metrics to detect control weaknesses and process failures early. This expectation is reflected in the Financial Conduct Authority’s guidance on monitoring and measuring outcomes, which emphasises proactive oversight rather than reactive correction.

Conclusion

In 2026, dispute performance is no longer determined by how aggressively merchants fight chargebacks. It is determined by how deliberately evidence is designed into the customer journey. The most effective merchants do not wait for disputes to occur before thinking about proof; they build systems that make evidence available, relevant, and timely by default.

The 2025 chargeback guidance reinforces this reality without stating it outright. Evidence quality now hinges on coherence, proportionality, and readiness. Order confirmation, delivery signals, usage availability, cancellation handling, and refund logic must all align to tell a single, credible story. When they do not, representation becomes expensive guesswork rather than a disciplined recovery process.

Crucially, “compelling evidence by design” changes how merchants decide which disputes to fight at all. Automation and pipelines make outcomes more predictable, allowing teams to refund early when losses are inevitable and defend selectively when success is likely. This not only improves win rates, but also reduces operational drag and ratio volatility.

The broader shift is strategic. Evidence has moved from being a reactive artefact to a form of infrastructure. Merchants that invest in this infrastructure spend less time assembling documents and more time preventing disputes altogether. They win more not by fighting harder, but by fighting smarter and by ensuring that many disputes never reach the point where a fight is required.

FAQs

What does “compelling evidence by design” mean in chargeback management?

It means building systems so that relevant evidence already exists before a dispute is filed, rather than trying to assemble documentation reactively under time pressure. Evidence becomes a product of system design, not last-minute effort.

2. Why is evidence design more important than prevention alone in 2026?

Because many disputes are inevitable. What has changed is how early outcomes are determined. Merchants with structured evidence pipelines can predict outcomes faster, refund strategically, and defend selectively with higher success.

3. How does the 2025 chargeback guidance change merchant expectations?

The guidance places greater emphasis on relevance, clarity, and timeliness of evidence rather than volume. It implicitly rewards merchants that standardise evidence capture and penalises ad-hoc or inconsistent submissions.

4. Are digital goods disputes harder to win than physical goods disputes?

They are more nuanced, not necessarily harder. Digital goods require proportional usage evidence that demonstrates access and availability without intrusive tracking. When designed correctly, this evidence can be highly persuasive.

5. When should a merchant refund instead of representing a dispute?

When evidence layers are incomplete, cancellation intent is clear, or the cost of recovery exceeds the transaction value. Automation helps enforce these decisions consistently rather than emotionally.

6. How do descriptors and receipts reduce unrecognised transaction disputes?

They act as recognition anchors. Clear, consistent descriptors and receipts help customers connect a transaction to a genuine purchase, reducing disputes driven by confusion rather than fraud.

7. What KPIs best indicate evidence maturity?

Time-to-evidence, representation win rate (interpreted selectively), and dispute root cause drift provide stronger insight than raw chargeback ratios alone.

8. Is evidence design relevant only for high-risk merchants?

No. While high-risk merchants feel the impact sooner, any merchant operating at scale benefits from predictable dispute outcomes, reduced operational drag, and improved customer trust.