By 2026, most chargeback losses are no longer caused by fraud alone. They are caused by misunderstanding.

Across payments teams, customer support desks, and even executive reporting, dispute terminology is used interchangeably—refund, reversal, chargeback—despite these being fundamentally different events with different risk, timing, and evidentiary consequences. The result is not just internal confusion. It is misclassified transactions, missed deadlines, and representation cases that fail before they are properly evaluated.

This matters because payment schemes do not interpret intent. They interpret language, timestamps, and system states. A transaction that is “refunded” in a merchant dashboard may still qualify as a chargeback under scheme rules. A “reversal” that happens too late may be treated as a loss, not a prevention. When merchants use the wrong terms or apply them at the wrong moment they often escalate disputes unintentionally.

As dispute volumes rise and schemes tighten enforcement, precision has become a risk control. Merchants that understand how refunds, reversals, and chargebacks are actually classified reduce losses without changing fraud rates. Merchants that do not often find themselves losing representation cases they never should have entered.

Getting the language right is no longer an accounting detail. It is a payment survival skill.

- Refunds, reversals, and chargebacks – what actually happens

- Timing terminology that changes scheme classification

- Reason-code language explained for merchants

- What “compelling evidence” really means

- Sector-specific dispute language (travel, subscription, digital goods)

- Common language mistakes merchants make

- Conclusion

- FAQs

Refunds, reversals, and chargebacks – what actually happens

Merchants often treat refunds, reversals, and chargebacks as interchangeable outcomes. Money leaves. The customer is satisfied. The case is “closed.” Inside payment networks, however, these events are processed very differently, and those differences determine whether a dispute is prevented, escalated, or locked into a loss.

The key distinction is not why the customer was unhappy. It is when and where the transaction was intercepted.

Refunds: merchant-initiated, but not always dispute-safe

A refund is a merchant action. It occurs after a transaction has settled and is pushed back through the same payment channel to the cardholder or account holder.

From a merchant perspective, refunds feel definitive. Funds are returned. The customer is informed. Support tickets are closed. The risk is assumed to be resolved.

From a scheme and issuer perspective, however, a refund does not automatically neutralise dispute rights. If a cardholder has already contacted their bank, or if the refund timing falls outside specific scheme windows, the transaction may still be eligible for a chargeback. In those cases, the refund becomes evidence but not a shield.

This is where merchants lose cases they believe should never have existed. The refund happened, but it happened too late or out of sequence to prevent escalation.

Reversals: pre-settlement, but highly time-bound

A reversal is fundamentally different. It occurs before settlement is finalised, intercepting the transaction while it is still moving between authorisation and clearing.

When reversals work, they are clean. Funds never fully post. No dispute is created. No representation clock starts. From a scheme perspective, the transaction effectively disappears.

The problem is that reversals operate inside extremely narrow timing windows. They rely on coordination between merchant systems, acquirers, and networks. Miss the window, and the transaction becomes settled at which point a reversal is no longer possible, regardless of merchant intent.

Many merchants believe they are issuing reversals when they are, in reality, issuing early refunds. That misunderstanding alone can be the difference between dispute prevention and dispute creation.

Chargebacks: issuer-initiated and procedurally rigid

Chargebacks are not a payment event. They are a dispute process.

Once a chargeback is initiated by an issuer, the transaction enters a governed workflow defined by scheme rules, deadlines, and evidentiary standards. At this point, merchant intent is largely irrelevant. What matters is classification.

Chargebacks create downstream effects that refunds and reversals do not:

- They generate reason codes

- They trigger representment deadlines

- They contribute to monitoring thresholds

- They carry reputational and financial penalties

This is why preventing a chargeback is categorically different from responding to one. Once a transaction is classified as a chargeback, the merchant is no longer controlling the flow they are responding to.

Why merchants conflate these events

The confusion is understandable. From a customer’s point of view, all three outcomes look similar: money comes back. From a merchant dashboard, they may even appear under the same “refunds” or “disputes” tab.

Internally, though, they live in different systems, follow different clocks, and trigger different liabilities. Treating them as synonyms flattens that complexity and that flattening is what leads to preventable losses.

Timing terminology that changes scheme classification

In dispute handling, timing is not a nuance. It is the mechanism that decides classification.

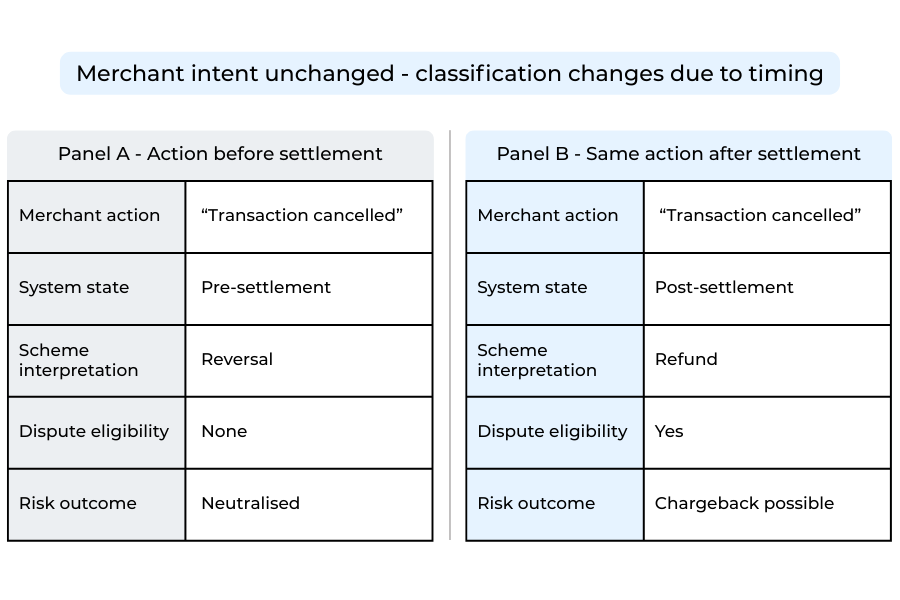

Merchants often believe disputes escalate because of why a customer complained. In practice, escalation usually happens because an action was taken at the wrong procedural moment even if that action was commercially reasonable. Payment schemes do not interpret fairness or intent. They interpret the transaction state.

The transaction lifecycle is the real decision tree

Every card transaction moves through a fixed sequence: authorisation, clearing, settlement. Scheme classification logic is anchored to that sequence, not to merchant workflows or customer communications.

Before settlement, merchant actions are preventative.

After settlement, the same actions become reactive.

This is why two identical outcomes of money returned to the customer can produce completely different dispute results. A transaction intercepted before settlement may never become disputable. The same transaction addressed minutes later may already be eligible for a chargeback, regardless of how quickly the merchant responds.

When “refund” stops meaning prevention

One of the most costly misconceptions is that issuing a refund automatically neutralises dispute risk.

If a cardholder contacts their issuer before the merchant action is completed, the dispute clock starts. From that moment onward, a refund no longer prevents escalation. It becomes supporting evidence within an issuer-controlled process. The classification has already shifted.

Merchants often overlook that dispute rights and consumer protections operate under statutory and scheme frameworks that are separate from internal refund policies. Understanding basic consumer protections around refunds can clarify why timing matters so much in dispute outcomes for example, UK consumer rights specify when refunds are due and when disputes may still be claimed after payment services have been completed.

This timing mismatch is why merchants frequently lose representation cases while believing they acted responsibly. The refund was real. The timing was not.

“Fast” is not the same as “in time”

Operational teams often optimise for speed: instant refunds, same-day resolution, automated cancellation. These metrics look positive internally but can be misleading externally.

Scheme logic does not measure responsiveness in hours or minutes. It measures whether an action occurred before or after a defined state change.

A refund issued minutes after settlement can still be “too late” to prevent classification as a chargeback, while a slower pre-settlement reversal can eliminate the dispute entirely.

This is where language becomes dangerous. Phrases like “instant refund” or “auto-cancelled payment” imply finality that may not exist in scheme terms.

How timing errors surface operationally

Timing-based misclassification rarely announces itself clearly. It tends to appear indirectly:

- Chargebacks filed despite visible refunds

- Unexpected reason codes on otherwise straightforward cases

- Representment losses attributed to “issuer discretion”

In reality, these outcomes are often deterministic. The system is doing exactly what it was designed to do based on timing markers the merchant failed to treat as risk-critical.

Why this keeps happening

Timing language is usually owned by operations or support teams, not risk teams. It is designed for customer reassurance, not scheme precision. Over time, these descriptions harden into internal truth, even when they diverge from how disputes are actually classified.

Merchants do not lose disputes because they ignore customers. They lose them because they misunderstand when prevention ends and response begins.

Treating timing terminology as a risk control not a reporting convenience is one of the fastest ways to reduce unnecessary chargeback escalation.

Reason-code language explained for merchants

Reason codes are often treated as administrative labels. In reality, they are issuer statements of belief.

When a chargeback is raised, the reason code does not simply describe what the customer said. It encodes how the issuer has classified the failure, what they believe went wrong, who they believe is responsible, and what type of evidence they expect to see in response. Merchants that misunderstand this language end up arguing the wrong case, even when the underlying facts are in their favour.

Reason codes describe assumptions, not accusations

A common mistake is to read reason codes emotionally. “Fraud”, “no-show”, or “services not rendered” are interpreted as accusations against the merchant or the customer. They are neither.

A reason code reflects the issuer’s starting assumption at the moment the dispute was raised. That assumption is shaped by timing, transaction data, and how the customer framed their complaint. It is not a verdict.

For merchants, the question is not “Is this fair?” but “What does this code assume happened?”

Why merchants lose by responding literally

Merchants often respond to reason codes at face value.

If the code says “fraud”, they submit proof of delivery.

If it says “refund not processed”, they submit a refund confirmation.

If it says “service not provided”, they explain their policy.

In many cases, that evidence is irrelevant to the issuer’s underlying assumption. The issuer may not be questioning whether delivery occurred, but whether authentication was strong enough. They may not be disputing that a refund exists, but whether it was processed within the correct window.

Literal responses feel logical internally. Procedurally, they miss the point.

Reason-code drift is a signal, not a coincidence

One of the most overlooked indicators of dispute health is reason-code drift.

When the same operational issue starts appearing under different reason codes, it is rarely because customer behaviour changed. It is usually because the timing or language changed. A delayed refund becomes “no refund received.” A cancellation after settlement becomes “services not rendered.” A weak authentication path becomes “fraud.”

Merchants that track disputes only by volume miss this entirely. Merchants that track language patterns see problems forming earlier.

The merchant mindset that works

Strong dispute teams stop asking, “What happened?”

They start asking, “What is the issuer assuming, and why?”

That shift changes how evidence is selected, how cases are prioritised, and when disputes are abandoned rather than fought. It also reduces wasted effort on unwinnable cases that only inflate operational cost.

Understanding reason-code language is not about memorising definitions. It is about recognising that disputes are decided on procedural interpretation, not narrative explanation.

What “compelling evidence” really means

“Compelling evidence” is one of the most misunderstood phrases in dispute management. Merchants often interpret it as volume: more documents, longer explanations, fuller timelines. In scheme logic, compelling evidence is not about completeness. It is about fitness whether what you submit directly addresses the issuer’s assumption encoded in the reason code.

This is why well-intentioned representation fails. The evidence may be accurate, but it answers a different question from the one being asked.

Compelling to whom, and for what purpose

Compelling evidence is compelling only in relation to a specific claim. Issuers assess evidence against a narrow test: does this materially contradict the reason the dispute was raised, using the standards and timeframes defined by the scheme?

If the dispute assumes unauthorised use, proof of delivery is rarely compelling.

If the dispute assumes a late or missing refund, customer communications may be irrelevant.

If the dispute assumes non-receipt of services, policy screenshots do not substitute for fulfilment proof.

The word “compelling” does not mean persuasive in a narrative sense. It means procedurally sufficient.

Evidence must match the dispute’s timing, not the merchant’s memory

A frequent failure point is temporal mismatch.

Merchants submit evidence that proves something happened just not when it needed to happen. A refund confirmation without a timestamp relative to settlement does not establish prevention. A cancellation email without confirmation of pre-settlement status does not establish reversal. Evidence that lacks timing context is treated as incomplete, even if it is otherwise accurate.

This is why evidence packs that look thorough internally can be dismissed quickly by issuers. They do not anchor claims to the moment that matters.

Why more evidence can weaken a case

Submitting excessive documentation often backfires.

Large evidence packs dilute signals. They force issuers to interpret relevance instead of verifying it. In some cases, additional documents introduce contradictions different dates, different terms, different interpretations that weaken an otherwise viable case.

Strong dispute teams curate evidence. They submit the minimum set required to meet the scheme test and nothing more. Brevity is not laziness; it is precision.

Compelling evidence changes by dispute type

What counts as compelling is not static across dispute categories.

For fraud-related disputes, issuers look for authentication strength and continuity of behaviour. For non-fraud disputes, they look for fulfilment proof and policy alignment. For refund-related disputes, they look for sequencing and timestamps.

Merchants that reuse the same evidence template across dispute types often fail because they assume consistency where schemes expect specificity.

The uncomfortable truth about unwinnable cases

Some disputes are unwinnable regardless of evidence quality.

If timing thresholds were missed, if mandatory data is absent, or if the reason code assumptions cannot be procedurally contradicted, no amount of documentation will change the outcome. Continuing to represent these cases increases cost without reducing loss.

Understanding what “compelling evidence” really means allows teams to make a harder but healthier decision: when not to fight.

Winning disputes is not about proving you are right.

It is about proving you meet the scheme’s test.

Sector-specific dispute language (travel, subscription, digital goods)

Dispute language does not operate in a vacuum. The same words trigger different assumptions depending on the sector involved. Issuers interpret disputes through a contextual lens shaped by typical customer behaviour, fulfilment models, and historical abuse patterns. Merchants that ignore this context often submit evidence that is technically correct but sector-inappropriate.

What follows is not a taxonomy. It is a translation guide for how dispute language is heard once it leaves the merchant’s system.

Travel: timing and expectation dominate everything

In travel, disputes are rarely about whether a transaction occurred. They are about when obligations crystallised and whether cancellation terms were unambiguous at that moment.

Merchants lose travel disputes not because services were unavailable, but because evidence fails to show that the customer accepted the timing and conditions before the point of no return.

Refund language is especially sensitive here. A “refund processed” after departure is rarely interpreted as remediation; it is interpreted as acknowledgement of a failure.

Subscriptions: consent and continuity are the core tests

Subscription disputes are fundamentally about authorisation over time. When reason codes reference “no authorisation” or “cancelled recurring transaction,” issuers are not questioning the original sign-up. They are testing whether consent persisted and whether cancellation mechanisms were accessible and honoured correctly.

Merchants often submit initial sign-up proof when the issuer is assessing post-sign-up behaviour. That mismatch is one of the biggest drivers of avoidable subscription losses.

Digital goods: delivery proof is necessary but rarely sufficient

Digital goods disputes expose the sharpest language gap between merchants and issuers.

Terms like “item not received” are frequently used even when delivery occurred instantly. Issuers interpret this language as a challenge to access, not transmission. Evidence that a file was delivered does not prove it was usable, accessible, or retained.

For digital goods, compelling responses tend to focus on:

- Account access continuity

- Usage or consumption signals

- Linkage between the purchaser and the consuming account

Merchants relying solely on delivery logs often find that disputes escalate despite technically flawless fulfilment.

Why sector fluency reduces losses

What unites these sectors is not complexity, but assumption.

Issuers bring default expectations to each category. Dispute language is filtered through those expectations before evidence is even reviewed. Merchants that align their responses to sector logic reduce friction immediately often without changing fraud rates or refund policies.

Sector-specific fluency does not require new tools. It requires recognising that the same words mean different things depending on what was sold.

Common language mistakes merchants make

Most dispute losses attributed to “scheme decisions” are, in reality, self-inflicted. They come from language that feels operationally sensible but is procedurally unsafe. These mistakes persist because they are embedded in dashboards, support scripts, and internal reporting long before a dispute ever reaches representation.

What follows are not theoretical errors. They are the phrases and habits that quietly turn manageable issues into chargebacks.

Treating customer reassurance as procedural truth

Support teams are trained to calm customers. Language like “we’ve refunded you” or “the payment has been cancelled” does that job well. The problem is that this language often migrates into internal systems and dispute notes as if it were a factual classification.

Schemes do not recognise reassurance. They recognise transaction state.

When internal language blurs that distinction, teams assume risk has been neutralised when it has merely been acknowledged.

Using internal statuses instead of scheme states

Many merchants rely on internal payment statuses that do not map cleanly to scheme logic. Labels such as “pending refund,” “voided,” or “closed” may be meaningful operationally, but they are meaningless or misleading once a dispute is raised.

This creates a false sense of control. By the time the discrepancy is discovered, the representation window is already narrowing.

Responding to reason codes emotionally

Words like “fraud” or “unauthorised” trigger defensive responses. Merchants rush to prove legitimacy instead of interrogating why that classification was applied.

The mistake is assuming the reason code is a judgement. It is not. It is a procedural starting point. Responding emotionally leads to irrelevant evidence, overlong submissions, and avoidable losses.

Over-explaining instead of proving

Narrative-heavy representation is another common failure.

Merchants attempt to tell the “full story” of a transaction, including context the issuer did not ask for. In doing so, they often bury the single fact that matters: timing, authentication strength, or fulfilment state under layers of explanation.

Schemes reward precision, not completeness.

Assuming refunds repair earlier mistakes

Refunds are frequently treated as a reset button. In dispute logic, they are not.

Once classification has occurred, a refund does not undo it. Continuing to frame refunds as corrective rather than evidentiary leads teams to fight cases they cannot win and miss the chance to prevent the next one.

The pattern behind these mistakes

All of these errors share a common root: merchants speak in customer language, but disputes are decided in system language.

Until that gap is acknowledged and managed deliberately, chargeback escalation will continue even in businesses with strong fraud controls and generous refund policies.

Conclusion

Disputes are not decided by intent, effort, or fairness. They are decided by language, timing, and classification.

By 2026, the mechanics of refunds, reversals, and chargebacks are no longer a back-office concern. They are a frontline risk control. Merchants that use dispute terminology loosely create ambiguity where payment schemes require precision and that ambiguity almost always resolves against them.

What this analysis shows is that most avoidable chargebacks do not stem from fraudulent customers or broken products. They stem from internal misalignment. Teams describe actions accurately in human terms but incorrectly in scheme terms. Refunds are assumed to prevent disputes. Evidence is submitted to explain rather than to qualify. Reason codes are treated as accusations instead of procedural signals.

Fixing this does not require new tools or stricter policies. It requires discipline in language.

When merchants align internal terminology with scheme logic, understanding when prevention ends, when evidence matters, and when a case is unwinnable, chargeback rates fall without changing customer experience. Refunds become deliberate, reversals are used correctly, and representation effort is focused where it can actually succeed.

In payments, words are not just descriptions. They are instructions to the system.

Merchants that learn to speak that language clearly will spend less time disputing outcomes and more time preventing them.

FAQs

1. Are refunds and chargebacks the same thing?

No. A refund is a merchant-initiated payment action, while a chargeback is an issuer-initiated dispute process. Even if a refund is issued, a chargeback can still occur if the timing or sequence does not meet scheme rules. Treating them as interchangeable is one of the most common causes of avoidable escalation.

2. Can issuing a refund always prevent a chargeback?

Only if it happens at the right time. Refunds issued after settlement, or after a cardholder has already contacted their bank, generally do not prevent chargebacks. In those cases, the refund becomes evidence rather than prevention, and the dispute process continues regardless.

3. What is the difference between a reversal and a refund?

A reversal intercepts a transaction before settlement is finalised, effectively stopping it from completing. A refund occurs after settlement and sends funds back through the network. From a dispute perspective, reversals are preventative; refunds are not guaranteed to be.

4. Why do merchants lose disputes even when they have “proof”?

Because evidence must be procedurally relevant, not just accurate. If evidence does not directly contradict the issuer’s assumption encoded in the reason code or does not meet timing requirements it will be rejected, even if it proves the merchant acted reasonably.

5. What does “compelling evidence” actually mean in practice?

It means evidence that directly satisfies the scheme’s test for that specific dispute type. Compelling evidence is precise, limited, and aligned to the reason code’s underlying assumption. More documents do not improve outcomes if they answer the wrong question.

6. Do reason codes tell merchants who is at fault?

No. Reason codes are not verdicts. They represent the issuer’s starting classification based on the information available at the time the dispute was raised. Merchants who treat them as accusations often respond incorrectly and weaken their own cases.

7. Why does dispute language vary by sector?

Issuers interpret disputes through sector-specific expectations. Travel disputes emphasise timing and cancellation terms, subscription disputes focus on ongoing consent, and digital goods disputes centre on access and usage rather than delivery alone. Using generic language across sectors increases loss rates.

8. How can merchants reduce chargebacks without changing their refund policy?

By improving internal language discipline. Aligning support scripts, dashboards, and dispute workflows with scheme terminology reduces misclassification, improves evidence selection, and prevents unnecessary escalation often without impacting customer experience.