Across Asia, stablecoins are no longer treated as speculative instruments in search of a use case. By 2026, regulators in the region are increasingly clear-eyed about what stablecoins are good for and, just as importantly, what they are not. Rather than attempting to retrofit them into everyday consumer payments, supervisory authorities are carving out narrowly defined roles where stablecoins solve genuine infrastructure problems without undermining monetary control or consumer protection.

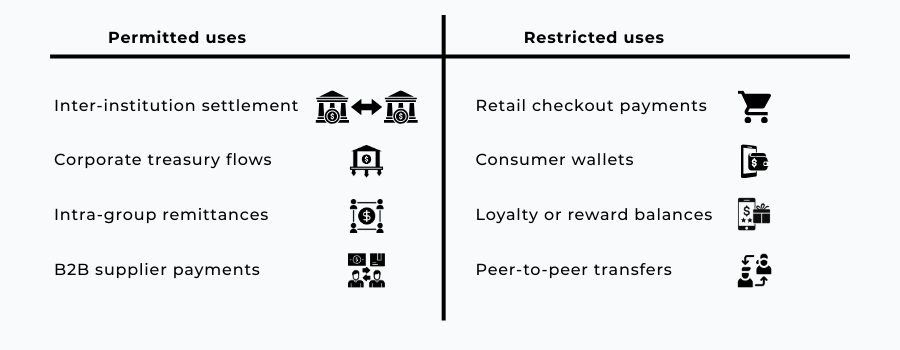

This pragmatic stance explains the apparent contradiction shaping Asian policy today. Stablecoins are being welcomed into settlement, treasury management, and certain cross-border flows, while remaining tightly constrained or explicitly excluded from retail payment rails. The distinction is not ideological. It reflects how regulators assess systemic risk, operational resilience, and behavioural exposure across different layers of the payments stack.

Where Stablecoins Are Being Allowed

Regulatory acceptance of stablecoins in Asia is not broad or abstract. It is specific, conditional, and closely tied to institutional use cases where the failure modes are understood and containable. Rather than approving “stablecoins” as a category, regulators are effectively approving functions with settlement sitting at the centre.

Settlement

Settlement is where stablecoins have found their strongest regulatory footing across Asia. This is partly because settlement already operates at a layer removed from consumer behaviour. Volumes are high, participants are professional, and controls are embedded contractually rather than socially.

In wholesale and quasi-wholesale environments, stablecoins offer something traditional correspondent banking struggles to deliver efficiently: near-instant finality across jurisdictions without relying on multiple intermediaries. For regulators, the attraction is not speed alone. It is predictability.

Stablecoin settlement models that gain approval in Asia tend to share common characteristics. They are permissioned rather than open-ended. Participants are known, vetted, and licensed. Redemption rights are clearly defined. Most importantly, the stablecoin does not attempt to replace fiat; it mirrors it temporarily, purely as a settlement instrument.

This distinction matters. Regulators are comfortable with stablecoins acting as a bridge between two regulated endpoints. They are far less comfortable when the bridge starts to look like a destination.

Treasury

Corporate and institutional treasury operations represent the second major area of acceptance. Here, stablecoins are treated less as payment instruments and more as liquidity management tools.

Large regional merchants, marketplaces, and platform businesses often hold balances across multiple currencies and jurisdictions. Moving liquidity between these pools can be slow, expensive, and operationally fragmented. Stablecoins offer a way to consolidate value temporarily, rebalance exposure, and redeploy capital without triggering repeated banking cut-off times or correspondent delays.

From a regulatory perspective, treasury use is easier to tolerate than retail payments because it is internal by design.

Funds are not circulating freely in the economy. They are moving within a closed operational loop, subject to internal governance, audit, and reconciliation controls.

Where regulators do intervene is at the edges: custody, valuation, and redemption risk. Stablecoins used for treasury are increasingly expected to sit within regulated custody frameworks, with clear segregation from operating funds and demonstrable access to underlying reserves.

Remittances

Remittances sit at the boundary of regulatory comfort and reveal where tolerance begins to thin.

Intra-group and B2B remittances are finding limited acceptance, particularly where traditional rails are slow or unreliable. Stablecoins can compress settlement cycles from days to minutes, reducing FX exposure and trapped liquidity. In regions with fragmented banking connectivity, this is a genuine efficiency gain.

Retail remittances, however, remain contentious. While the technology can reduce costs, regulators are wary of introducing consumer-facing crypto rails into cross-border flows that are already sensitive from an AML and sanctions perspective. The risk is not just illicit finance. It is dispute resolution, error recovery, and consumer recourse once funds leave a regulated domestic perimeter.

As a result, most Asian regulators are drawing a line: stablecoins may power remittance infrastructure behind the scenes, but not serve as the user-facing value store or transmission mechanism for consumers.

Jurisdictional Snapshots

While the regional pattern is broadly consistent, individual jurisdictions apply it with different emphases. Understanding these nuances matters for any merchant or payments business operating across Asia.

Singapore

Singapore has taken the most explicit approach to stablecoin regulation, not by endorsing widespread use, but by defining what acceptable stablecoins look like. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) has focused on reserve quality, redemption rights, and issuer governance effectively treating qualifying stablecoins as narrow-purpose settlement instruments rather than general money.

What stands out in Singapore’s approach is restraint. Approval is conditional, not promotional. Stablecoins are permitted where they enhance financial market efficiency without creating parallel monetary systems.

Retail use is not banned outright, but it is tightly constrained by licensing, disclosure, and consumer protection requirements that most stablecoin models struggle to meet at scale.

The result is a framework that encourages institutional experimentation while discouraging mass-market adoption by default. This clarity has made Singapore a hub for infrastructure-focused stablecoin activity, without opening the door to uncontrolled consumer usage.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong’s stance reflects its role as an international financial centre with a strong emphasis on market integrity. Stablecoins are assessed primarily through the lens of financial stability and investor protection, rather than payments innovation.

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority has signalled openness to regulated stablecoin issuance, but only within a tightly supervised perimeter. Licensing expectations are high, particularly around custody, governance, and operational resilience. Retail distribution is treated cautiously, with a clear expectation that consumer-facing activity must meet standards comparable to traditional stored value facilities.

In practice, this has channelled stablecoin development toward settlement, capital markets infrastructure, and institutional liquidity management areas where Hong Kong already has deep regulatory experience.

Japan

Japan remains one of the most conservative jurisdictions in Asia when it comes to retail crypto exposure, and stablecoins are no exception. Regulatory thinking here is shaped by a strong preference for bank-centric financial systems and clear legal classifications of money-like instruments.

Where stablecoins are tolerated, they are typically issued or intermediated by licensed banks or trust companies, and framed as digital representations of deposits rather than independent payment instruments. This model effectively neutralises many of the risks regulators associate with stablecoins, but also limits their flexibility.

Japan’s approach underscores a broader regional theme: stablecoins are acceptable when they reinforce existing financial architecture, not when they attempt to bypass it.

Why Retail Use Remains Restricted

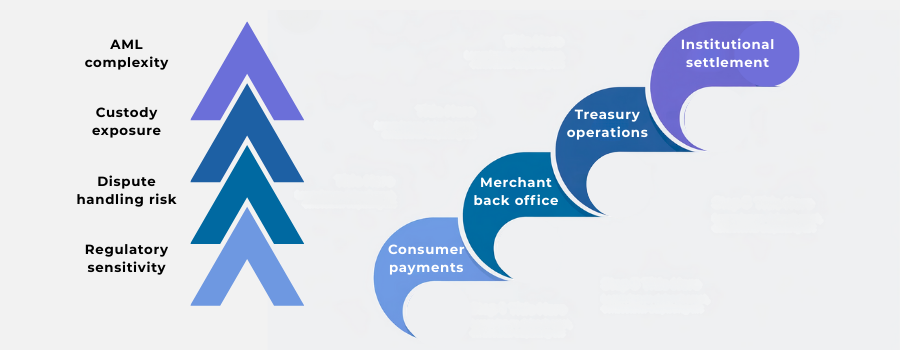

Retail payments sit at the most sensitive edge of the financial system. They are where regulation, consumer behaviour, and monetary policy collide. This is precisely why Asian regulators have drawn such a firm boundary around stablecoins in consumer-facing contexts even as they permit the same instruments deeper inside the stack.

At a structural level, retail payments are designed around reversibility, predictability, and social trust. Consumers expect transactions to be correctable. Merchants expect disputes to follow defined processes. Regulators expect accountability to sit with identifiable, licensed entities. Stablecoins, by contrast, are engineered for finality. Once value moves, it settles. That feature is attractive in wholesale settlement. In retail, it is a mismatch.

The problem is not merely technical, It is behavioural. Retail payments amplify human error. Wrong amounts, wrong recipients, compromised credentials, misunderstood fees these are normal events at scale. Traditional payment systems absorb this friction through chargebacks, error correction frameworks, and consumer protection rules. Stablecoins, especially when held or transmitted directly by users, bypass much of this safety net.

There is also a regulatory asymmetry that matters. When a consumer uses a card, bank transfer, or domestic wallet, the regulator has leverage over every party involved: issuer, acquirer, PSP, and bank. When a consumer uses a stablecoin wallet, that chain often collapses into software, custody, and protocol governance areas where enforcement is harder and remediation slower.

Beyond consumer protection, monetary considerations play a quieter but decisive role. Retail stablecoin adoption creates the conditions for functional currency substitution, even when the stablecoin is fully backed. If households begin to hold and transact in private digital money, central banks lose visibility into payment velocity, deposit stability, and stress behaviour. In economies that prioritise financial stability and capital controls, this is not an acceptable trade-off.

This is why regulatory language across Asia tends to converge on the same outcome, even when expressed differently. Stablecoins may exist. They may be regulated. They may even be redeemable at par. But their role is not to become everyday money.

Instead, regulators are signalling a clear separation of layers:

- Stablecoins as infrastructure, used by institutions under supervision

- Fiat-based instruments as retail money, governed by consumer-first rules

The distinction is deliberate. Allowing stablecoins to cross it would require re-engineering consumer protection, dispute resolution, and monetary oversight frameworks from the ground up. Asian regulators have shown little appetite for doing that when existing payment systems already function well.

From a policy perspective, restricting retail use is not a rejection of innovation. It is an assertion of priorities. Efficiency gains at checkout are marginal. The cost of destabilising consumer trust in payments is not.

PSP & Bank Integration Models (Second Rewrite No Bullets)

Integration Happens Where Customers Never Look

In Asia, stablecoin integration inside banks and PSPs is designed to be unnoticed. This is not a failure of imagination. It is a deliberate alignment with regulatory expectation.

Regulators have signalled that stablecoins may exist within payment systems only if they do not change how money is experienced by consumers or merchants. The more invisible the token, the easier it is to supervise. The more visible it becomes, the harder it is to reconcile with existing accountability frameworks.

As a result, most integration efforts treat stablecoins as internal settlement instruments rather than payment options. Transactions are still authorised in fiat. Balances are still reported in fiat. Customer contracts still reference fiat obligations. Stablecoins merely move value between institutions after those obligations are fixed.

Bank-Led Models Favour Containment Over Reach

Where banks are involved directly, the design philosophy becomes even more conservative.

Stablecoins are structured to resemble deposits rather than instruments in their own right. Transferability is limited. Redemption rights are explicit. Circulation outside approved counterparties is often prohibited by design.

This approach allows banks to explore tokenised settlement without conceding control over liquidity, customer protection, or monetary alignment. It also reflects a deeper regulatory instinct: innovation is acceptable when it reinforces existing financial architecture, not when it competes with it.

PSP-Led Models Optimise Operations, Not Products

Payment service providers approach stablecoins from a different angle. Their motivation is rarely ideological. It is operational.

Cross-border settlement between regional entities can be slow, capital-intensive, and difficult to reconcile. Stablecoins offer a way to compress settlement timelines and reduce prefunding without altering front-end payment flows.

Crucially, these models remain inward-facing. The stablecoin does not belong to the merchant. It does not belong to the consumer. It belongs to the PSP’s operational stack. This containment is what keeps regulators engaged rather than resistant.

Where Integration Proposals Break Down

Integration efforts tend to stall when stablecoins are positioned as customer-facing choices rather than institutional tools.

When a model introduces optional stablecoin settlement at checkout, or allows consumers to hold balances directly within a PSP environment, regulators begin to question who carries responsibility when something goes wrong. Dispute resolution, safeguarding, and AML accountability become fragmented, and the proposal loses its footing.

The issue is not technical feasibility. It is governance clarity.

The Quiet Rule Behind Every Approved Model

Across jurisdictions and integration types, one unstated rule dominates regulatory thinking: stablecoins may optimise processes, but they must not redefine money.

As long as banks and PSPs respect that boundary, integration remains possible. When they attempt to cross it, even cautiously, progress slows or stops altogether.

AML, Custody & Licensing Expectations

If stablecoins are being tolerated by Asian regulators at all, it is because they are being forced to conform to familiar control frameworks. This section is where regulatory pragmatism becomes most visible. There is little appetite for bespoke crypto-era rules. Instead, supervisors are mapping stablecoin activity onto existing expectations around financial crime, asset protection, and authorised activity.

How Regulators Frame the Core Control Areas

Rather than treating AML, custody, and licensing as separate conversations, Asian regulators increasingly view them as interdependent. Weakness in one area is assumed to compromise the others.

| Control area | Regulatory focus | What this means in practice |

| AML & transaction monitoring | Traceability and attribution | Every stablecoin movement used in settlement or treasury must be linked to identifiable, risk-rated entities, with monitoring standards comparable to traditional payment rails |

| Custody & safeguarding | Control of private keys and reserves | Regulators expect institutional-grade custody, clear segregation of assets, and demonstrable access to underlying reserves in stress scenarios |

| Licensing & authorisation | Accountability and supervision | Stablecoin activity must be anchored to entities already subject to regulatory oversight, not operated through loosely defined technical roles |

This framing explains why many stablecoin initiatives stall at the design stage. A model that looks efficient from a technology perspective can quickly become untenable once mapped against these three lenses simultaneously.

AML: Familiar Expectations, Applied Relentlessly

From an AML perspective, regulators are largely uninterested in novelty. Stablecoin transactions used by banks or PSPs are expected to meet the same standards as any other payment flow: customer due diligence, ongoing monitoring, and the ability to investigate suspicious activity end to end.

What regulators resist is the idea that blockchain transparency alone substitutes for compliance. Transaction visibility without attribution is not sufficient. Pseudonymous wallets, even in permissioned environments, introduce investigative friction that supervisors are unwilling to accept at scale.

Custody: Where Technical Risk Becomes Regulatory Risk

Custody is where stablecoins face their most intense scrutiny.

Private key management, access controls, operational resilience, and recovery planning are no longer viewed as purely technical matters. They are treated as prudential concerns. A custody failure is assumed to have consumer and systemic implications, even if the stablecoin is not consumer-facing.

This is why regulators increasingly expect stablecoin custody arrangements to resemble traditional safeguarding models, with clear legal ownership, segregation from operating funds, and independent oversight.

Licensing: The Anchor Point Regulators Will Not Relinquish

Licensing is the mechanism that makes everything else enforceable.

Asian regulators have shown little tolerance for stablecoin models that rely on diffuse responsibility or technical intermediaries operating outside formal authorisation. Whether through payments licences, trust frameworks, or digital asset regimes, stablecoin activity must sit within a perimeter supervisors already understand.

This is also why many “hybrid” models struggle. If no single entity can be held accountable for AML failures, custody losses, or redemption breakdowns, the model is unlikely to progress beyond pilot stage.

The Underlying Regulatory Logic

Taken together, these expectations reveal a consistent logic. Stablecoins are not being assessed as revolutionary instruments. They are being assessed as risk containers. Their acceptability depends on whether regulators can see inside them, control their failure modes, and assign responsibility when things go wrong.

As long as those conditions are met, stablecoins can exist within Asia’s payments ecosystem. When they are not, regulatory tolerance ends quickly.

Merchant Use Cases That Actually Work

Most merchants encounter stablecoins first as an abstract promise: faster settlement, lower fees, global reach. In practice, the use cases that survive regulatory scrutiny and operational reality are far narrower and far more mundane.

This is not a failure of imagination on the merchant side. It is the consequence of where risk is allowed to sit. In Asia, stablecoins only work for merchants when they reduce friction inside the business, not when they change how customers pay.

Where Stablecoins Fit Naturally

The most viable merchant use cases are internal by design. They operate away from checkout flows, customer support desks, and consumer-facing terms and conditions.

Large, multi-entity merchants with regional footprints are the clearest example. Managing liquidity across subsidiaries in different jurisdictions is slow and capital-intensive. Stablecoins can act as a temporary aggregation layer, allowing value to be repositioned without triggering repeated banking delays.

In these scenarios, stablecoins are not treated as revenue. They are treated as operational inventory held briefly, reconciled tightly, and redeemed predictably.

Another area where stablecoins can make sense is supplier settlement, particularly when counterparties are already operating within regulated digital asset environments.

Settlement cycles can be shortened, FX exposure reduced, and reconciliation simplified. The key condition is symmetry: both sides understand the instrument, the risk, and the redemption mechanics.

What These Use Cases Have in Common

Although they appear different on the surface, workable merchant use cases share a set of underlying traits:

- No direct consumer exposure

- Limited holding periods

- Clear redemption paths

- Known counterparties

- Contractual governance

These traits are not accidental. They are what allow stablecoins to exist within existing merchant risk frameworks without forcing a redesign of compliance, accounting, or customer protection processes.

Where Merchants Tend to Overreach

Problems arise when merchants attempt to move stablecoins closer to the customer.

Accepting stablecoins directly for goods or services introduces complexity that often outweighs any perceived benefit. Price volatility, even in nominally stable instruments, creates accounting challenges. Refunds and disputes become operationally awkward. Customer expectations around error resolution collide with the finality of on-chain settlement.

Loyalty schemes and incentive programmes built on stablecoins face similar issues. What looks like engagement innovation quickly becomes a regulated stored value problem, complete with licensing, safeguarding, and disclosure obligations.

In short, the closer stablecoins get to the point of sale, the more they behave like regulated money and the less tolerant regulators become.

A Practical Merchant Test

Merchants evaluating stablecoin use can apply a simple internal test.

If the use case:

- Touches customer funds

- Requires customer education

- Creates new refund or dispute pathways

- Alters how prices are displayed or settled

Then it is likely misaligned with how Asian regulators currently view stablecoins.

If, instead, the use case:

- Sits within treasury or operations

- Reduces friction between existing entities

- Preserves fiat-facing customer experiences

Then it is far more likely to be viable.

The Strategic Implication

Merchants that succeed with stablecoins do not talk about them publicly. They do not brand them. They do not offer them as features.

They treat stablecoins as internal tooling useful, contained, and replaceable. This mindset aligns closely with regulatory expectations and reduces the risk of being pulled into unintended supervisory conversations. In Asia, stablecoins reward discretion more than ambition.

Risk Boundaries Merchants Must Respect

Stablecoins do not usually fail merchants because the technology breaks. They fail because boundaries blur slowly, then all at once. What begins as an internal efficiency experiment can drift into regulated territory without anyone noticing until a bank, PSP, or regulator asks an uncomfortable question.

This section is not about hypothetical risk. It reflects the lines Asian regulators are already enforcing, even when they are not always written explicitly.

Boundary One: Stablecoins Must Not Become Customer Money

The fastest way to attract regulatory scrutiny is to let stablecoins start behaving like customer funds.

The moment a customer can hold value, wait for a refund, or perceive a balance as “theirs,” the merchant inherits consumer protection expectations that stablecoin infrastructure is not designed to meet. Finality becomes a liability. Custody becomes ambiguous. Dispute handling becomes structurally weak.

Merchants often underestimate how little distance there is between “internal settlement” and “stored value” in regulatory terms.

Boundary Two: Responsibility Cannot Be Abstracted Away

Many stablecoin models rely on technical intermediaries, wallet providers, protocol operators, custodians each responsible for a fragment of the flow. Regulators do not accept fragmented accountability.

From a supervisory perspective, someone must be responsible for:

- Onboarding decisions

- Transaction monitoring outcomes

- Asset safeguarding

- Failure remediation

If a merchant cannot clearly identify where those responsibilities sit and prove that the responsible party is licensed the model is already on unstable ground.

Boundary Three: Cross-Border Assumptions Are Dangerous

A stablecoin use case that works in one jurisdiction does not automatically travel well.

Asian regulatory regimes may align in philosophy, but they diverge in execution. What is tolerated as treasury tooling in one market may be interpreted as unauthorised payment activity in another. Merchants operating regionally must assume that regulatory acceptance resets at every border. The mistake is treating stablecoins as globally neutral instruments. Regulators do not.

Boundary Four: Speed Does Not Excuse Visibility Gaps

Stablecoins are often justified internally on the basis of speed. Faster settlement. Faster access to liquidity. Faster reconciliation.

Speed, however, does not compensate for reduced visibility. Regulators expect transaction traceability, auditability, and investigatory access to be preserved or improved relative to traditional rails. Any efficiency gain that weakens those controls is unlikely to survive regulatory review.

Boundary Five: Optionality Creates Risk

Allowing stablecoins as an “option” alongside fiat payments is often framed as a low-risk experiment. In reality, optionality multiplies complexity.

Parallel flows mean parallel compliance, parallel reconciliation, and parallel failure scenarios. For most merchants, this creates operational risk without strategic upside.

Asian regulators tend to see optional consumer-facing stablecoin acceptance not as flexibility, but as ambiguity and ambiguity is rarely tolerated in payments.

The Pattern Merchants Miss

Across enforcement actions, supervisory feedback, and quiet regulatory conversations, a consistent pattern emerges.

Merchants get into trouble not by using stablecoins but by letting them drift into roles they were never approved to occupy.

The safest stablecoin strategies are narrow, reversible, and boring. They optimise processes without redefining obligations. They respect the fact that regulatory tolerance in Asia is conditional, contextual, and easy to lose.

Conclusion

By 2026, Asia’s position on stablecoins is no longer ambiguous. Regulators are not debating whether stablecoins can exist. They have already decided where they belong.

They belong behind the scenes, embedded in settlement layers, treasury flows, and tightly governed cross-border operations. They belong in places where participants are known, risk is contained, and failure does not spill directly into consumer harm. This is why regulators are willing to engage, experiment, and even formalise frameworks in these areas.

Asian regulators are signalling quietly but consistently that consumer payments already work. They are fast, trusted, reversible, and embedded in mature protection regimes. Introducing stablecoins at checkout does not meaningfully improve that experience, but it does introduce new forms of risk that regulators would then be expected to manage.

This distinction matters for how merchants, PSPs, and banks should think about strategy.

Stablecoins are not a growth lever. They are not a branding opportunity. They are not a shortcut around licensing or banking relationships. Treated that way, they attract scrutiny disproportionate to their benefit.

Treated correctly, stablecoins become something far less glamorous and far more useful: infrastructure.

Infrastructure is invisible when it works. It is constrained by design. It exists to support systems that already have legitimacy, not to replace them. That is the mental model Asian regulators are applying and it is the model that viable stablecoin strategies must align with.

The future of stablecoins in Asia will not be decided at the checkout page.

It will be decided in settlement logic, governance structures, and risk boundaries that most customers will never see.

And that is exactly how regulators intend it to stay.

FAQ

1. Are stablecoins banned for retail payments in Asia?

In most Asian jurisdictions, stablecoins are not explicitly “banned” for retail use, but they are effectively constrained by regulatory expectations that make widespread consumer adoption impractical. Requirements around licensing, safeguarding, dispute resolution, and consumer protection mean that most retail-facing stablecoin models struggle to operate compliantly at scale. Regulators have chosen restriction through control rather than outright prohibition.

2. Why do regulators trust stablecoins for settlement but not for consumers?

Settlement involves professional counterparties operating under contractual obligations, defined governance, and regulatory oversight. Retail payments, by contrast, involve consumer error, behavioural risk, and political sensitivity when things go wrong. Stablecoins are well suited to environments where finality is an advantage; retail payments require reversibility and consumer recourse, which stablecoin infrastructure does not naturally provide.

3. Can merchants legally accept stablecoins from customers in Asia?

In theory – yes, in practice, it is rarely viable. Accepting stablecoins directly from customers can trigger payment licensing, stored value obligations, and consumer protection requirements that many merchants are not prepared to meet. Even where technically permissible, the compliance burden often outweighs the commercial benefit.

4. Do stablecoins reduce cross-border costs for Asian merchants?

They can, but only in specific contexts. Stablecoins are most effective for internal treasury movements, intercompany settlement, or supplier payments between sophisticated counterparties. Once consumer-facing acceptance is introduced, cost savings are often offset by increased operational, compliance, and reconciliation complexity.

5. How do Asian regulators view stablecoin custody risk?

Custody is treated as a prudential issue, not a technical one. Regulators expect institutional-grade controls over private keys, asset segregation, and recovery processes. Any stablecoin model that cannot demonstrate clear ownership, safeguarding, and redemption rights is unlikely to be tolerated within regulated payment environments.

6. Are bank-issued or bank-intermediated stablecoins treated differently?

Yes. Stablecoins that resemble tokenised deposits and are issued or intermediated by licensed banks tend to face less resistance. This is because they fit more comfortably within existing supervisory frameworks and preserve clear accountability. Independent or freely circulating stablecoins face much higher scrutiny, especially in retail contexts.

7. Will stablecoins eventually be allowed at checkout in Asia?

Regulators have not ruled this out permanently, but there is little indication it is a priority. Asian payment systems already deliver speed, reliability, and consumer protection. Unless stablecoins can materially improve retail outcomes without introducing new risks, regulatory appetite for checkout adoption is likely to remain low.